| About Us | Contact Us | Calendar | Publish | RSS |

|---|

|

Features • latest news • best of news • syndication • commentary Feature Categories IMC Network:

Original Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: ambazonia canarias estrecho / madiaq kenya nigeria south africa canada: hamilton london, ontario maritimes montreal ontario ottawa quebec thunder bay vancouver victoria windsor winnipeg east asia: burma jakarta japan korea manila qc europe: abruzzo alacant andorra antwerpen armenia athens austria barcelona belarus belgium belgrade bristol brussels bulgaria calabria croatia cyprus emilia-romagna estrecho / madiaq euskal herria galiza germany grenoble hungary ireland istanbul italy la plana liege liguria lille linksunten lombardia london madrid malta marseille nantes napoli netherlands nice northern england norway oost-vlaanderen paris/Île-de-france patras piemonte poland portugal roma romania russia saint-petersburg scotland sverige switzerland thessaloniki torun toscana toulouse ukraine united kingdom valencia latin america: argentina bolivia chiapas chile chile sur cmi brasil colombia ecuador mexico peru puerto rico qollasuyu rosario santiago tijuana uruguay valparaiso venezuela venezuela oceania: adelaide aotearoa brisbane burma darwin jakarta manila melbourne perth qc sydney south asia: india mumbai united states: arizona arkansas asheville atlanta austin baltimore big muddy binghamton boston buffalo charlottesville chicago cleveland colorado columbus dc hawaii houston hudson mohawk kansas city la madison maine miami michigan milwaukee minneapolis/st. paul new hampshire new jersey new mexico new orleans north carolina north texas nyc oklahoma philadelphia pittsburgh portland richmond rochester rogue valley saint louis san diego san francisco san francisco bay area santa barbara santa cruz, ca sarasota seattle tampa bay tennessee urbana-champaign vermont western mass worcester west asia: armenia beirut israel palestine process: fbi/legal updates mailing lists process & imc docs tech volunteer projects: print radio satellite tv video regions: oceania united states topics: biotechSurviving Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: canada: quebec east asia: japan europe: athens barcelona belgium bristol brussels cyprus germany grenoble ireland istanbul lille linksunten nantes netherlands norway portugal united kingdom latin america: argentina cmi brasil rosario oceania: aotearoa united states: austin big muddy binghamton boston chicago columbus la michigan nyc portland rochester saint louis san diego san francisco bay area santa cruz, ca tennessee urbana-champaign worcester west asia: palestine process: fbi/legal updates process & imc docs projects: radio satellite tv |

printable version

- js reader version

- view hidden posts

- tags and related articles

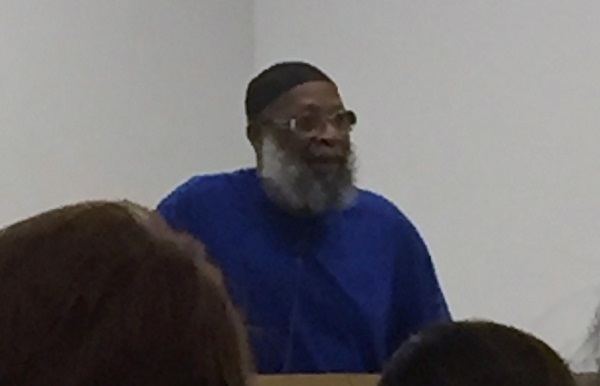

View article without comments Liberated Political Prisoner Sekou Odinga Speaks Outby Rockero Friday, Mar. 11, 2016 at 5:39 PMrockero420@yahoo.com Wednesday, February 10, 2016

"In the name of Allah, the magnificent, the merciful, I bear witness that there is no God but God, lord of all the world, and I bear witness that Muhammad ibn Abdullah is His slave servant and last prophet.

"As said, my name is Sekou Mbgozi Abdullah Odinga [...] I was born in New York in 1944. I'm 71 years old now. I've been trying to struggle for the love of my people, for the survival of my people--for the survival of all people--because those who we struggle against are those who threaten the survival of this world. I've been struggling since the mid 60s, when I was a young man. I think I was about nineteen. When I was 20 years old I joined the Organization of Afro-American Unity that was started by Malcolm X. "I learned about Malcolm X while I was a youngster in one of the youth prisons in New York. I think I was about sixteen years old at the time. I was given a three-year sentence. When I come home after about 30 months, I come home looking for Malcolm to see if he was all we were told he was, and so to see if I could get with him and help--help him with the struggle that he said he wanted to be in. "I did that. At about the same time that I did that, he was assassinated. So I spent very little time with that organization. The people that took over that organization after his demise wasn't exactly as revolutionary as he was. I didn't think, at least, that they was headed in the same direction that he was. So I joined these other young brothers and sisters and tried to implement the organization that we thought he was trying to build, and we started in our local neighborhood in Queens, New York. "While struggling with them, we learned about what used to be called the anti-poverty program. Which was an organization in New York--well, was mostly through all the ghettoes--and we came up to try to slow down the rebellions that was going through the communities. We were having, each year--'specially in the summer--we were having what they called a "long, hot summer" where young people were rebelling against the conditions that they seen: the abuse and the terror and the murder by the police. The terrible housing that some of us had to live in. Lack of food, lack of clothing, poor education, poor recreation, you name it--all the things that you see today. The same things that existed in the 60s when I was coming up in the struggle. And I dare say it existed in the 40s and the 30s and the 20s and you can go on back and it's always been there. The conditions have always been bad and it's the conditions we were struggling to try and change, try and make better. Try to create programs to survive these conditions. "Because of those in the leadership of the program that I was a part of, we couldn't seem to get money for the program. I was in charge of the youth. I was a youth myself! I was only about 21 at the time. I was in charge of bringing youth programs to our community. Mostly youth, young men, and women, between the ages of twelve and fifteen. Course I could never get funds for the program that I tried to create. Eventually I found myself looking for something else. That was around the same time that I first heard about the Black Panther Party. "In 1967 or '66--I don't remember exactly when it was--when they went into Sacramento, here in California, with guns to protest people trying to take the guns from them. We thought, from looking at what they were doing and from reading about them, that the organization that they were part of, the Black Panther Party, would be a better vehicle for us to struggle for us. We come to California--well, we sent three brothers here To California to check them out. We decided that we would work to try to build the New York chapter. Around the same time, leaders from the Black Panther Party came to New York to try to establish the New York chapter of the Black Panther Party. "I joined them early. I think I might've been at the first meeting that they had when I joined the Black Panther Party. I became the leader of the Bronx section of the Black Panther Party. Along with the leader in Harlem, we became the Harlem-Bronx chapter, 'cause our resources were so short at the time, that we could afford but one office. And we worked out of that for about a year before it got so big that we just had to get another office. "And though most of us--especially the men who joined the organization--joined to struggle against the police brutality and terror going on in our community, we soon found it that there were so many more problems in the community that the people demanded that we take up--that we do something about the housing, hunger, the education, welfare, medical...and we started creating programs to deal with these issues. We started feeding children breakfast before they went to school. We had clothing drives where we would go to the cleaners in our neighborhood and ask them to donate the clothes that people had not gone to pick up in six months or a year, whatever their dates were for deciding that they weren't going to come back. Those in the neighborhood that were small markets, we would go to the markets and stores and ask for food. We were able to get food to feed our children, and we were also able to give or packages once a month of groceries to families. We were able, too, to get the stores--the department stores in the neighborhood--to give us clothes that, we used to call them the 'seconds,' that they might have a stitch missing or a button missing or something like that. And for the most part, most of them agreed with us, and gave us these clothes, and gave us this food, and we were able to give them out to the community. "That caused a contradiction with the powers that be! Cause at the same that that we was giving these clothes out, we were having local education--local education sessions for the community--to point out these contradictions. Why is it that, here we are, a bunch of young people that we don't have anything--we can feed our children, and our government can't? We can demand decent housing for our people, and our government don't do that? We can stand up when someone is brutalized by the police in the community and demand that they stop, and our mayor wasn't doing that. You know? So these contradictions cause the powers that be to really come at us, to attack us. And because of those attacks from the powers that be, so many of us wind up going to jail or going underground, and many was killed. Hospitalized, brutalized. "In 1969, April of 1969, 21 members of the Black Panther Party leadership was targeted by COINTELPRO counterintelligence program, was locked up for a lot of ridiculous charges, such as blowing up botanical gardens and stuff like that. Ridiculous stuff, but it was a purpose behind it. They knew what they were doing. The reason they did this is because this 21 cadre was some of the leading cadre of the Black Panther Party at the time. And we had denounced, not only were they not there to continue to struggle, to continue to organize, to continue to serve he people, that those who were left behind had to struggle to get them out. Had to struggle to get money to pay for lawyers. Had to struggle to raise money for bails. Had to struggle to raise money to help feed he families, cause many of them, because many of them were the sole provider for their families. So instead of serving the people as he had been doing, we was caught up now basically working to free our political prisoners. Which they all were political prisoners. Cause they were attacked and locked up cause of the political work that they were doing. So even though we eventually, after two years, won all the cases--everybody was found not guilty of everything--by that time, so much had happened that all of those programs basically was dead almost. In New York at least. And we was put in a position to try and rebuild. There was four of us, and one of them was me, myself included, who was not captured at the time of the New York 21. They actually didn't get 21 of us; they only got seventeen. I went underground, underground meaning that I left New York, changed my name, changed my persona, and started working in another state doing some of the same work while carrying on a front that I was somebody else. "While I was doing that, I was asked by my leadership here in the Black Panther Party would I go to Afrika to help organize the international section of the Black Panther Party. We went over there to try to gather information about other struggles. Algeria, North Afrika, which is where I was at, at the time was a newly liberated country, a very revolutionary country who had invited revolutionary people from around the world--invited them to come to Algeria to set up offices so that they could onto hue to work and could continue to disseminate information about what they were doing to the rest of the world, they could gather information about what was going on around the rest of the world. That was our job. If the Black Panther Party was to try to get information to the rest of the world about what was going on and how we were struggling here in Amerika, and to gather information about the struggles in the rest of the world, especially in Afrika, Asia, Latin Amerika/South Amerika. We did that for a few years--a couple of years, actually. It was actually we was there for about four years, maybe, but we were only able to really work openly for about two years, when, by that time, the government here in the United States put enough pressure on the Algerian People Government to quiet us--to stop our work. They refused to turn us over to the government, but they did demand that we let them censor any information that we were going to send back to Amerika, which basically meant that we were about out of business. So that's when I decided to come back to Amerika. "During the time that I had been in Afrika, the Black Liberation Army had been organized. There were number of brothers and sisters around the country struggling in small groups to demand an end to the police brutality and murders and demand the end to the attacks being brought on the Black Panther Party and the other progressive organizations around the country and I joined in with some of those that was around the Northeast area--New Jersey, New York, Philadelphia--that area and continued my work. During that time, one of the operations we dealt with--let me just say here, that some of the work that we done was of a military nature. not everything was of a non-violent nature. We always believed that in not only in self-defense, but also in offense if that was necessary. We had read the different laws, the international laws, such as the treaty that was signed in the UN, and treaties such as the Geneva conventions, which this country had signed, which gave the right to colonial subjects and oppressed people to struggle by any means necessary, including arms. Because this country signed those treaties, that made that the law of this land. So we felt that we were within our legal rights to defend ourselves if attacked, and if necessary, to go on offense sometimes. Which some of us did. Some of my comrades--many of my comrades were captured, many of them were killed. At one point there was three of them attacked on the New Jersey turnpike. Sundiata Acoli, Zayd Shakur, ans Assata Shakur. One of them was killed, one of them was shot, and the other was captured and brutalized and locked up. When Assata Shakur, being one of the ones that was shot, she was shot up on the arm. She had her arm up, went through her shoulder, wind up in the hospital. They tortured her while she was in the hospital. They would come through and stick they finger in the hole where she had been shot at. And just did just vicious things to her. But anyhow, to make a long story short, after she was released, she went to trial for a number of different things. I think she went to seven trials. She was able to beat six of them. The last one, which was the death of a New Jersey police officer, she was found guilty after the third trial by an all-white jury of murdering a police officer although she had her hands in the air. Anyhow, she was one of those that we were able to go in and bring back out. She was in a state prison in New Jersey that was kinda lax in their security and the opportunity kinda presented itself, and we "seized the time" as we used to say, and I was blessed to be one of the ones that actually went in to bring her out. After a couple of years of that struggle, I mean after a couple of years of her coming out, being able to evade the different police organizations and get to a area where she was welcomed and could live semi-open, which was Cuba, I continued my work here. After about two years later, while trying to aid another comrade, who had just got--well, he hadn't just git caught up., He had been in a military operation where he was wounded and he needed help. I was asked to come help him try to get out of New York. While on our way out, we were detected, surrounded, captured, and he was murdered while surrendering on his stomach while laying in the street. They waled up behind him and put a bullet in his head. I was brought in, I believe, because they didn't know who I was. I had been gone for thirteen years, nobody had seen me for thirteen years, so I believe that was what allowed me to be taken in. "I was brought in, tortured for about seven hours, beaten, burn with cigars, toenails--not all of them, but one of them, toenails ground off and pulled out. Waterboarded, head flushed down toilets. Eventually taken into a court where the judge refused to allow an arraignment cause the condition I was in. He forced them to take me to a hospital. I was take to the hospital where I stayed for the next three months trying to recover from the torture. Before I was able to recover, completely heal, they took me out, put me on trial in New York state for a number of different charges. Quite a few, actually. In Rocklin county I had about six charges, in Queens I had about eight charges, stemming form the day I was captured, the day I was captured. The one in Rocklin County was the the case that they were looking for the man that I was trying to help get out. It was a expropriation of a bank--of an armored truck. Eventually I was bale to get out of the case up in Rocklin County cause one of our traitor was so good to tell them that I wasn't there--that I was somewhere else. So they took me out of that case and put me on trial in the federal system. "I was put on trial in the federal system for a number of expropriations and the liberation of Assata Shakur. I was found guilty both in New York and in the federal system. I was found guilty of two charges in the federal system of the eleven that they charged me with. One of them was the liberation of Assata Shakur, adn the other one was the expropriation of an armored truck, I was found guilty in New York State of six counts of attempted murder of police stemming from my capture the day that I was captured although no police was hurt, scratched, the only person that was brutalized was me, and the only person murdered was my comrade. But anyways, I was given 25-to-life for that. One sentence was supposed to run after the other sentence was complete, so in fact, I guess I was given sixty-five years-to-life. Because of some technicalities that they made, some things that they did wrong that I was able to point out--it took me some thirty years to get back into court but when I did get back into court, I was able to show the judge and the judge agreed with ,me that there were some things that they had did wrong. He ruled that, although he wouldn't rule that he was gonna release me, he said the mistakes that they made, he would just try to right those mistakes by running both sentences together rather than separately. And he basically ordered them to take me to the parole board and release me, which is why I'm here today. "Since coming out, I've been working diligently to try to bring some attention to other political prisoners. We have lots of political prisoners in Amerika. In the movie we just seen, they said it was more than seventy. Well there's a lot more than seventy. There's at least several hundred. There's a lot of us that don't recognize at least some of the political prisoners in this country. But they have many political prisoners coming from other countries. This country goes around the world picking up people that they think MIGHT be dangerous, bringing them to this country, putting them on trial, usually find them guilty, In fact I've never heard of a case where they've brought someone from Iraq or Iran or Afghanistan or Syria or Libya or any of the East Afrikan countries where they have brought people from. All of them I've met, I met a lot of them in Florence, Colorado, the Maxi-jail that the federal system has in this here country, you'll find many, many of them there. Some of them, they say clearly that they are there cause of things that they said, not things that they've done. Because they say that they support--supported people that say they're our enemies. Said they support Al-Qaeda or ISIS or anybody else that they don't like, that they find, that they declare a terrorist. Some of them, A lot of them, don't even speak the language, so for them to fight their case was almost impossible. They're away from their families, their away from their loved ones, they're away from their support, and most of us never hear about them. You know>? Besides them, there's many others here, from our own movements. The Black Liberation Movement, Black Panther Party, from the Native America Struggles, AIM, from the Puerto Rican struggles, the Chicano struggles. We have political prisoners that we just don't bother to find out about, but they're right here, But we need to support these people. These are the people that fight for us, that continue to struggle for us, even in there. They give their lives for us. They sacrificed they family, they sacrificed everything to struggle for their people. We owe them. We owe them. We owe them the right to be supported. We owe them our support. We should be willing. We're the only people I've met that don't recognize our political prisoners and the people that struggle for us. We jumped up and cheered when Nelson Mandela was released, and he had did the exact same thing that many of our political prisoners had done, and we didn't find no problem in saying that he was all right, but we won't recognize the people right here that did the same thing. And we don't support them. They come right out of your neighborhoods. We have political prisoners right here in California. You need to go onto the internet and find out who these political prisoners are, and support them. "Write them a letter. Send their support committee a dollar. Get with 'em. Try to ask them, 'what can we do to help?' There's a site called jericho.com, jerichomovement.com, where you'll find all of our--when I say 'our,' I'm talking about the Black Panther Party, the Black Liberation soldiers, you'll find all of them on the Jerichomovement.com. Most of them you've seen in that there slide show that we just showed. They need our support--they need your support. Many of them are now going to up for parole. The parole board is told by those that oppose them that the community don't want them back into the community, that they community is afraid of them, that the community--all kind of negative things that I don;t believe is true. And you should let the parole board know that that ain't true. Write the parole boards. You can find out whose going on parole and when they're going on parole by looking on these sites. Write the comrades that are in these prisons and ask them what you can do for them. Find out who their families are. Write they families, call they families and ask what you can do for them. You can take somebody and give them a ride to see they families. You can send them a dollar. Or you can just call 'em and talk to 'em, cause sometimes they just want to know the people understand what they're going through. Maybe you can help them by just saying, 'Hey, how you doing today?' Just thought I'd call you and see how you were doing cause I know your loved one is away and in prison and the pressures that put on you. You know? So there's many things you can do if you want to, and I think you should do something. If you not gonna pick up the mantle that they dropped, or was knocked out of their hands, you can at least say, 'I support what you did. I understand what you did. I understand that we have problems here and that you were struggling to deal with those problems. That's what I come here to tell you today mainly, that let's support our political prisoner.s Let;s support our prisoners of war. Let's make sure that they know we care about them and that we haven't forgotten them. Most of them are old now. They getting up in their sixties, seventies, and some of them in their eighties. They done did twenty-five-thirty, thirty-five-forty, forty-five-fifty years. That's enough time! I don't care what they done! That's enough time! They did it! Even if you don't agree with what they done, you must agree that thirty-five years is enough time for whatever they done. So I ask you for their support. I ask you for your support. Support our political prisoners. Let's free 'em all.": He then took a moment to recognize the crowd and to allow us to participate. A young woman was the first to do so: "I just want to thank you for your courage, and for all your personal sacrifices you made for us. I just want to thank you for that. There's not enough thanks that I can give you. I don't have enough words. But it's a blessing to meet you and its a blessing that you're here with us and that you remind us of some of the things we need to do. Thank you." The followed a question about the money sent to political prisoners: "People are so very skeptical about what happens with the money. So did you feel that money actually got to you in prison, if it comes to you through whatever means, through whatever organization, or whatever? Do you feel that it got to you?" He answered: "Yes, all the money that was actually sent to me through my support committee, got to me or my family. Course it got to them. And my son, and my wife was the head of my support committee. He still is the head of it, cause we still try to raise money for others, ans so it still exists. And they are the heads my support committee. So yes, I feel that all of it came to me, if it came through that way, then it got to me." The questioner followed up: "So every political prisoner has like a support committee?" "Many of 'em do, but everyone don't. Some of 'em need the support. They need people to build support committees. I just recently built one--trying to build one for Veronza Bowers who is in Georgia. He's been in jail for forty-some years, even though he finished his time eleven years ago, homeland security snatched him on his way out the door and they locked him up cause they think he's a threat to us. At least that's what they claim they think. But no, all of them don't. Kamau Sadiki, who is the father of Assata Shakur's child, her daughter, when he finished his time in the late 90s, they tried to get him to go to Cuba so they could snatch her. When he refused, they threatened him with a life sentence. He continued to refuse. They came up with an old case that they hadn't solved, they put it on him, found him guilty, and they gave him that life sentence that they had threatened him with. He now languishes in very bad health in the state jail in Georgia, and no, he don;t have a support committee. And there's others that don't have support committees. A number of them do have support committees. like I said if you go to Jericho Movement, you can write and ask them. If they don't maybe you would be good to start one for 'em. They need 'em. I'm gonna do whatever I can for 'em but I definitely can't do it all. And there's others that 's doin' what they can for them, but we need your help. We need you to step up and aid and support." The next audience member then spoke: "I also want to thank you for your work, and for your sacrifice, and I'm really hearing the call to action. I just want to let folks know that since Obama is on his way out, this is the last couple of months that he can issue clemency to any of our prisoners who are held in federal penitentiaries, so now is the time to really, really, increase the pressure on him specifically. He's coming to California this weekend. He's gonna be in Palm Springs out in the Coachella Valley to meet with some leaders of South Asian countries to talk about the Trans-Pacific Partnership. We don't care why he's there--we're there to say free the political prisoners. We're working with the members of the American Indian Movement-Southern California. Course their main concern is freedom for Leonard Peltier, but we are also in contact with Puerto Rican Alliance to have someone speak about Oscar L�pez Rivera, and also some of the political prisoners that are held in Mexico and Guatemala, US citizens but obviously opposing the same empire, Nestora Salgado and Ta�o L�pez down in Guatemala. They have local connections here. Ta�o L�pez's sister lives in Rialto, so we're bringing the political prisoner issue to the president, directly, in Palm Springs. And I think, from what I understand, he's also going to be doing some fundraising in LA, so I think some of the folks who were previously associated with the Jericho chapter of LA along with, probably, Black Cross, are also going to be making sure that message is heard. So I also want to make an invitation to anybody here that also cares about the freedom for our political prisoners to join us on Monday, February 15 out in Palm Springs. "I've read a lot about the writings of many of the political prisoners, and I notice that a lot of people start in kind of a vague--maybe Black nationalism, or just a love for their community, and there's a progression many of them take. Some of them like Kuwasi Balagoon became an anarchist, New Afrikan Anarchist. There's, like, H Rap who became a very devout Muslim, others who have kind of followed other paths, you know, ideologically. I was wondering what your take on that change in the thoughts, maybe that imprisonment has brung, or just maturity maybe, and if you have any words about your own development as a thinker, either from your political experience or your experience of being in prison." "I think that, those of us who have been down, especially if you've been down for a long period of time, you have a long time to think and to kind of decide which direction you want to go. And so different people go different directions. Myself, I did become--I was a Muslim when I went in, but I wasn't what I would call a devout Muslim. I didn't make my prayers every day. I didn't do a lotta things I shoulda did if I called myself a Muslim. As I got more into it in prison, did more studying about it, I had time to really now do that type of study, and I committed myself to become a better Muslim, and I continue to try to do that. And so, I guess what you're asking is, how people develop. They develop many different ways, you know, depending on their own leaning--what strikes them. One of the things that I've found that all of the political prisoners that I've known that went in there, almost all of them continue to struggle while they was in there and when they come out, no matter what particular direction they might've curved into. They principles and their love for their people never left them. You mention Jamil Al-Amin, if you go into what he did once he came out of prison, he cleaned up the whole west end of Atlanta, Georgia. It was a dope business down there, you could go down there at any time of day or night and never have to worry about it, you know? And so, even though he was a Muslim, he kinda continued the struggle to do things to make his community and this a better world. That is the commitment of all political prisoners--a love for people and a love for activism, to actually do something other than talk about it." The next audience member spoke: "Thank you so much again for your wonderful words and also the call to action other people have mentioned. Thank you for taking the time--not just to be here, but also for the years of time you have put in. You know, in the video, I just keep hearing over and over again about time, years, years, years. And what's kind of difficult for me is like, in the erasure of political prisoners, how much time they've put in, is this kind of story, in the society, and all over the place, is how everything is different, and its so much better now. And even though we're actually living it not being any better, there's so much pressure on people constantly to say, 'it's better now! It's better now! It's better now!' And in that insistence we kind of forget that people are still doing time, because it's not better." "No, it's not. And we have to reclaim, or we have to claim the narrative. We allowed other people to put forward our narrative and say how things is with us and how things should be with us. We have to change that! Which means we have to step up and we have to do our research and do our due diligence in finding out what's going on, and then become active. And you don't have to become active in no kinda military way--there's so much that needs to be done. In fact, I would discourage people from trying to become active in any kind of military way right now because you up against the most militarized country that's ever been. Things we need to do--our power, the power that we really have, is the people power. If we can organize enough people, we can make this country, make this government that's supposed to be of the people actually be of the people, and we can demand that they free all political prisoners. We can demand that instead of putting a trillion dollars into that war machine, that they put them into these schools, that we really get universal health care instead of having to go through what we go through to try to get some kind of health care. We can demand that we have decent housing. This country actually generates enough funds to do that. We just don't take--we the people--don't force them to do with our taxes what they needed to be doing with our taxes." The next person asked where he had summoned up so much courage. Odinga replied that most of the young people are already very courageous. "It's not courage that's lacking. It's direction." The professor who opened the talk asked about legal strategies and the political use of the courtroom. Odinga did lament that some of the politicization of the proceedings may have resulted in harsher sentences for defendants who were ultimately imprisoned, especially in his case. "If I had to do it over again, I would still take a political position, but I would take it in a different way than I did. I would really fight the charges. Course the politics really did win the jury over on our side. But it worked for everybody else but me." There were further questions about the Republic of New Afrika and political education, but perhaps the most poignant response came to the question, "Has your philosophy of Black revolution and liberation changed?" To which the elder responded with a simple, "No."

Report this post as:

Audio from Sekou Odinga lectureby Rockero Friday, Mar. 11, 2016 at 9:08 PMrockero420@yahoo.com audio: MP3 at 71.4 mebibytes Download the MP3 and listen and/or broadcast on your local pirate, low power FM, community, or educational radio station.

Report this post as:

|