| About Us | Contact Us | Calendar | Publish | RSS |

|---|

|

Features • latest news • best of news • syndication • commentary Feature Categories IMC Network:

Original Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: ambazonia canarias estrecho / madiaq kenya nigeria south africa canada: hamilton london, ontario maritimes montreal ontario ottawa quebec thunder bay vancouver victoria windsor winnipeg east asia: burma jakarta japan korea manila qc europe: abruzzo alacant andorra antwerpen armenia athens austria barcelona belarus belgium belgrade bristol brussels bulgaria calabria croatia cyprus emilia-romagna estrecho / madiaq euskal herria galiza germany grenoble hungary ireland istanbul italy la plana liege liguria lille linksunten lombardia london madrid malta marseille nantes napoli netherlands nice northern england norway oost-vlaanderen paris/ĂŽle-de-france patras piemonte poland portugal roma romania russia saint-petersburg scotland sverige switzerland thessaloniki torun toscana toulouse ukraine united kingdom valencia latin america: argentina bolivia chiapas chile chile sur cmi brasil colombia ecuador mexico peru puerto rico qollasuyu rosario santiago tijuana uruguay valparaiso venezuela venezuela oceania: adelaide aotearoa brisbane burma darwin jakarta manila melbourne perth qc sydney south asia: india mumbai united states: arizona arkansas asheville atlanta austin baltimore big muddy binghamton boston buffalo charlottesville chicago cleveland colorado columbus dc hawaii houston hudson mohawk kansas city la madison maine miami michigan milwaukee minneapolis/st. paul new hampshire new jersey new mexico new orleans north carolina north texas nyc oklahoma philadelphia pittsburgh portland richmond rochester rogue valley saint louis san diego san francisco san francisco bay area santa barbara santa cruz, ca sarasota seattle tampa bay tennessee urbana-champaign vermont western mass worcester west asia: armenia beirut israel palestine process: fbi/legal updates mailing lists process & imc docs tech volunteer projects: print radio satellite tv video regions: oceania united states topics: biotechSurviving Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: canada: quebec east asia: japan europe: athens barcelona belgium bristol brussels cyprus germany grenoble ireland istanbul lille linksunten nantes netherlands norway portugal united kingdom latin america: argentina cmi brasil rosario oceania: aotearoa united states: austin big muddy binghamton boston chicago columbus la michigan nyc portland rochester saint louis san diego san francisco bay area santa cruz, ca tennessee urbana-champaign worcester west asia: palestine process: fbi/legal updates process & imc docs projects: radio satellite tv |

printable version

- js reader version

- view hidden posts

- tags and related articles

Condoleezza Rice Challenged on War and Torture at Stanfordby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AMStanford University students, staff, alumni, and community have called for Condoleezza Rice to be held accountable for war crimes and torture. Challenging her return to the University, they are petitioning for a probe into her alleged violations of international and U.S. law.

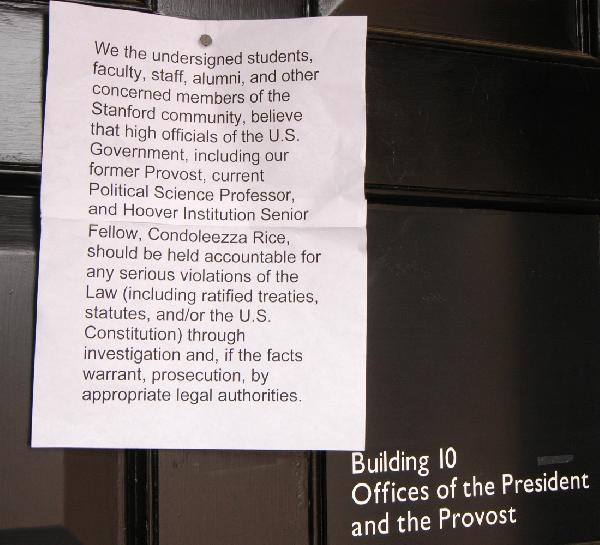

Through video, students speak truth to power When former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice went to a student dormitory to have an informal discussion on April 27, 2009, she never thought it would put her back into the national spotlight. Speaking with Stanford students in Roble Hall, Rice categorically denied any personal role in authorizing harsh interrogation techniques and denying that waterboarding is torture. Sophomore Reyna Garcia recorded the entire conversation on her video camera and posted 7 minutes of it on YouTube [1]. Within a week, the video clip had been viewed 185,000 times and had received over 2000 posted comments. Mainstream local and national media picked up to story, interviewing the two students in person and by telephone. In the video, Jeremy Cohn, a junior in public policy, pressed Rice by making a comparison between Bush Administration policies and World War II, saying, “we did not torture the prisoners of war [in World War II].” Rice retorted, “And we didn’t torture anybody here either.” Cohn: “We tortured them in Guantánamo Bay.” Rice: “No. No dear, you’re wrong. You’re wrong. We did not torture anyone. And Guantánamo Bay, by the way, was considered a model ‘medium security’ prison by representatives of the Organization of Security Cooperation in Europe who went there to see it. Did you know that?” Cohn: “Were they present for the interrogations?” Rice: “No. Did you know that … Just answer me. Did you know that the Organization of Security Cooperation in Europe said Guantánamo was a model medium security prison?” Cohn: “No, but I feel that changes nothing.” “Did you know that?” Rice insisted. She went on the conclude, “Do your homework first!” Beyond flat denials, Rice persisted in avoiding the difficult discussions on whether the now widely-acknowledged “harsh interrogations” constitute torture, or how such methods could be justified on “enemy combatants” when they are prohibited against “prisoners of war” or prisoners in the United States. Another student asked, “Is waterboarding torture?” Rice: “The President instructed us that nothing we would do would be outside of our legal obligations under the Convention against Torture [2]. And, by the way, I didn’t authorize anything. I conveyed the authorization of the Administration to the Agency that they had policy authorization subject to the Justice Department’s clearance. That’s what I did.” Student: “Is waterboarding torture?” Rice: “I just said. The United States was told – we were told, ‘nothing that violates our obligations under the Convention against Torture.’ And so by definition, if it was authorized by the President, it did not violate our obligations under the Convention against Torture.” The immediate response on the Internet was comparison to former president Richard Nixon’s infamous statement to David Frost in 1977, “Well, when the President does it, that means it is not illegal.” This justifiably perked national media interest. Reflecting on his conversation with Rice, Jeremy Cohn commented that evening, “she tried to convince me that ‘no torture’ occurred at Guantánamo, again telling me to ‘do my homework.’ Well unfortunately for her I’ve done my homework. This article [http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/jan/03/guantanamo.usa] links to FBI files detailing mistreatment at Guantánamo. Rachel Maddow even had a former prison guard from Guantánamo Bay on her show a few weeks ago talking about torture at Guantánamo Bay.” Cohn observed, “Eventually Professor Rice had to leave for her dinner with other students. My first response was of disappointment she had spoken very surely and at points condescendingly. However, after consulting all of my sources and re-examining the information, I felt re-affirmed in everything that I had said. She had left trying to make me look bad. Fortunately the truth is on my side.” Rice in the hot seat When Condoleezza Rice left the departing Bush Administration after eight years of government service, she imagined returning quietly to private life at Stanford University, where she previously was a professor of political science and university provost. In an interview given to the Stanford Report (an official weekly university newspaper, January 28, 2009), Rice said, “I really don't know what to expect, but Stanford is my home. I'm comfortable on the campus. I hope pretty soon to get out among students. I love going over to the houses or the dorms and having dinner and having a question-and-answer session afterward.” Under President George W. Bush, Rice was National Security Advisor from January 2001 to January 2005 and thereafter Secretary of State until January 2009. She was present in the many crucial meetings with the President, Vice President Richard B. Cheney, Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld, and her predecessor, then Secretary of State Colin L. Powell that led to the U.S. invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the launching of the so-called “war on terror,” and the subsequent decisions to authorize waterboarding and other physical methods of interrogation of “enemy combatants.” According to a classified document released by Attorney General Eric Holder on April 22, 2009 at the request of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Condoleezza Rice met then CIA Director George Tenet on July 17, 2002 to “advise that the CIA could proceed with its proposed interrogation of Abu Zubaida” subject to approval by the Justice Department [3]. The Justice Department, in turn, relied heavily on the legal rationalizations outlined in the memos of University of California law professor John Yoo and federal judge Jay Bybee, which have now been widely repudiated. While Rice takes shelter in being only the messenger, the same Justice Department document indicates that Rice and four other administration officials were first briefed in May 2002 on “alternative interrogation methods, including waterboarding.” This is long before Powell, Rumsfeld, and even Cheney became involved according to the Justice Department timeline. Thus, with Rice having unique early high-level access to what was going on and being planned, her early acceptance of these policies was central to the decision to authorize them. Justice Department documents have also revealed that Abu Zubaida was waterboarded at least 83 times, and Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was waterboarded 183 times, quantitative evidence of deliberate, persistent, and prolonged abuses. Context of protest – what the national media ignored What the mainstream media ignored was the wider context of opposition and protest on the Stanford campus and in the community. As Rice was arguing her case inside Roble Hall protected by a half dozen Secret Service agents, scores of students and community members were gathered outside to raise their concerns about Condoleezza Rice’s automatic return to Stanford University. For her critics what is most troubling is not her opinions, but the foregone conclusion by the University that she should be honored without question with such a prestigious chair as the Thomas and Barbara Stephenson Senior Fellow on Public Policy at the Hoover Institution. The case against Rice is outlined in a letter to the Stanford community by the student organization, Stanford Says No to War [4] and an article in The Stanford Progressive [5]. Daniel Mathews, a graduate student in mathematics, emphasized that what is at stake is not academic freedom and freedom of speech because “we can respectfully and politely disagree.” He continued, “But here today … we have a professor who did not merely advocate for brutalities like waterboarding – but authorized them. A professor who did not merely cheerlead for war, but was involved in official planning and propaganda efforts of that war, at the highest levels. These are not things to respectfully disagree about. These are not experiences to learn from. These are crimes to be prosecuted.” Two protesters adorned orange jumpsuits and black hoods to remind students entering Roble Hall about Condoleezza Rice’s role in authorizing waterboarding, other harsh interrogation methods, extraordinary rendition, and indefinite detentions. Handwritten banners demanded “prosecute torturers” and “no war criminals.” While eating pizza, students, staff, alumni, and members of the community listened to speakers call for change in the way Stanford and other universities so readily honor top government policy-makers with prestigious academic chairs without apparent regard to the crimes they may have committed while in high office. Mathews cautioned, “In calling for prosecutions, we are not looking for retribution. The most important thing is to make sure that the horrible episodes we have seen – war, torture, aggression, violations of international law – do not happen again. How do you ensure they do not happen again? By letting anybody who is thinking of doing it again know that if they do it again, they will be prosecuted. And how do you ensure that? By prosecuting those who did it this time.” When Condoleezza Rice and fellow former Secretary of State George Shultz showed up for a second dinner discussion with a limited number of students at Wilbur Hall on May 12, 2009, they were again greeted by protests quietly reminding Rice to “do her homework,” about her role in the road to war and torture, and about Shultz’s role in the Iran-Contra fiasco. Meanwhile, other students organized “Condival” in White Plaza on May 1, 2009 as a carnival parody on Condoleezza Rice’s role the “race to war,” waterboarding (for apples), “Abu Ghraib ring toss,” and other games that are “so much fun that it’s a war crime.” Some students thought Condival “went too far” and was “in bad taste,” but hundreds of students participated in having “fun raising awareness on campus.” Petition When Stanford Says No to War began circulating a petition calling for Condoleezza Rice to be held accountable for potential war crimes, Stanford alumni also took up the cause. A weekend fortieth anniversary reunion of the April Third Movement (A3M) brought together nearly 150 Stanford alumni who were student activists against the Vietnam War in 1969. The final event of the reunion was a press conference for presenting the petition to the University. It reads: “We the undersigned students, faculty, staff, alumni, and other concerned members of the Stanford community, believe that high officials of the U.S. Government, including our former Provost, current Political Science Professor, and Hoover Institution Senior Fellow, Condoleezza Rice, should be held accountable for any serious violations of the Law (including ratified treaties, statutes, and/or the U.S. Constitution) through investigation and, if the facts warrant, prosecution by appropriate legal authorities.” [6] Marjorie Cohn, President of the National Lawyers’ Guild, explained the purpose of the gathering and press conference: “By nailing this petition to the door of the President’s office, we are telling Stanford that the university should not have war criminals on its faculty. There is prima facia evidence that Rice approved torture and misled the country into the Iraq war. Stanford has an obligation to investigate those charges.” Cohn went on to emphasize that the call to investigate Rice is not a denial of academic freedom. Every faculty member has a right to express ideas and opinions, she said. But this does not apply to violating international and constitutional law. Then Lenny Seigel, Stanford alumnus of the class of 1970, with hammer in hand, nailed the petition onto the door of the office of Stanford President John L. Hennessy in Inner Quad Building 10. The practice of nailing a petition to the door of a university office follows an historic precedent set in October 1968 when students nailed a document on the door of the office of the Stanford Board of Trustees demanding that Stanford “halt all military and economic projects and operations concerned with Southeast Asia.” The action launched a campaign that led to the formation of the April Third Movement in the spring of 1969. Notes 1.

Video clip by Reyna Garcia, YouTube, 27 April 2009, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijEED_iviTA 2.

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading

Treatment or Punishment, adopted by the U.N. General Assembly on 10 December

1984, http://www2.ohchr.org/English/law/cat.htm 3.

R.J. Smith and P. Finn, “Harsh methods approved as early as summer

2002,” Washington Post, 23 April 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/04/22/AR2009042203141.html 4.

“Condi Coalition Letter to Stanford Community,” 16 April 2009,

http://www.stanford.edu/group/antiwar/cgi-bin/mediawiki/index.php?title=Condi_coalition_letter_draft 5.

Daniel Mathews, “Prosecuting Condoleezza Rice,” The Stanford

Progressive, January 2009, http://progressive.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/article.php?article_id=271 6.

Sign the Stanford Community Petition at http://www.stanford.edu/group/antiwar/crpetition.html

Report this post as:

Protest against Condoleezza Rice at Roble Hallby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Human rights activists in orange jumpsuits like those worn by prisoners at Guantánamo Bay protest Condoleezza Rice’s presence at Stanford University in front of Roble Hall on April 27, 2009.

Report this post as:

Condoleezza Rice with student Jeremy Cohnby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Rice insisted, “We did not torture anyone.” The reception in Roble Hall at Stanford University was limited to residents of the dormitory.

Report this post as:

Rice scolding Cohnby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Rice condescendingly put down Cohn’s question about authorizing torture, saying, “No. No dear, you’re wrong. You’re wrong.”

Report this post as:

Unexpected heroesby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Stanford undergraduate students Jeremy Cohn and Reyna Garcia never imagined the national media attention they would receive for simply wanting to inform the Stanford community and the public about what a former National Security Advisor really thinks about controversial government policies. (Photos as they appeared on CBS 5)

Report this post as:

Protest against Rice at Roble Hallby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Graduate student, Daniel Mathews, speaking to students about why Condoleezza Rice should be investigated for possible war crimes.

Report this post as:

Protest against Rice at Roble Hallby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Students discuss Condoleezza Rice’s probable role in authorizing harsh interrogations that may have violated international law against torture.

Report this post as:

Protest against Condoleezza Rice and George Shultzby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Banners outside Wilbur Hall on May 12, 2009 question the presence of “war criminals” on campus.

Report this post as:

Secret Service guard “private event” at Wilbur Hallby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Silent protesters are reflected in the windows of the dining room where Rice and Shultz spoke while Secret Service agents stood outside.

Report this post as:

Condivalby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Stanford students created a carnival atmosphere on May 1, 2009 to mock Condoleezza Rice’s return to Stanford.

Report this post as:

Condivalby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Students enact a parody on the Bush administration’s “race to war” in which Condoleezza Rice, as National Security Advisor, played a crucial decision-making role.

Report this post as:

Condivalby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

“Race to war” includes “going through” the U.N. Security Council (empty cardboard boxes).

Report this post as:

Condivalby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

As the “race to war” emerges with “mission accomplished,” it is greeted with “Thank you, liberators!”

Report this post as:

Condivalby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Waterboarding for apples.

Report this post as:

Condivalby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Abu Ghraib ring toss.

Report this post as:

Press conferenceby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Called by Stanford alumni meeting for the weekend to mark the fortieth anniversary of the April Third Movement against the Vietnam war, Lenny Siegel announces a petition calling for investigation of Condoleezza Rice for possible war crimes.

Report this post as:

Alumni announce petitionby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Lenny Siegel and Marjorie Cohn explain the petition to be presented to Stanford President John Hennessy.

Report this post as:

Nailing petition to investigate Riceby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Siegel and Cohn nail the petition initiated by Stanford Says No to War to the door of the offices of Stanford’s president on May 3, 2009.

Report this post as:

Petitionby Sharat G. Lin Tuesday, May. 19, 2009 at 4:40 AM

Petition nailed to the door of Stanford President John L. Hennessy demands that Condoleezza Rice be “held accountable for any serious violations of the Law.”

Report this post as:

|