| About Us | Contact Us | Calendar | Publish | RSS |

|---|

|

Features • latest news • best of news • syndication • commentary Feature Categories IMC Network:

Original Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: ambazonia canarias estrecho / madiaq kenya nigeria south africa canada: hamilton london, ontario maritimes montreal ontario ottawa quebec thunder bay vancouver victoria windsor winnipeg east asia: burma jakarta japan korea manila qc europe: abruzzo alacant andorra antwerpen armenia athens austria barcelona belarus belgium belgrade bristol brussels bulgaria calabria croatia cyprus emilia-romagna estrecho / madiaq euskal herria galiza germany grenoble hungary ireland istanbul italy la plana liege liguria lille linksunten lombardia london madrid malta marseille nantes napoli netherlands nice northern england norway oost-vlaanderen paris/Île-de-france patras piemonte poland portugal roma romania russia saint-petersburg scotland sverige switzerland thessaloniki torun toscana toulouse ukraine united kingdom valencia latin america: argentina bolivia chiapas chile chile sur cmi brasil colombia ecuador mexico peru puerto rico qollasuyu rosario santiago tijuana uruguay valparaiso venezuela venezuela oceania: adelaide aotearoa brisbane burma darwin jakarta manila melbourne perth qc sydney south asia: india mumbai united states: arizona arkansas asheville atlanta austin baltimore big muddy binghamton boston buffalo charlottesville chicago cleveland colorado columbus dc hawaii houston hudson mohawk kansas city la madison maine miami michigan milwaukee minneapolis/st. paul new hampshire new jersey new mexico new orleans north carolina north texas nyc oklahoma philadelphia pittsburgh portland richmond rochester rogue valley saint louis san diego san francisco san francisco bay area santa barbara santa cruz, ca sarasota seattle tampa bay tennessee urbana-champaign vermont western mass worcester west asia: armenia beirut israel palestine process: fbi/legal updates mailing lists process & imc docs tech volunteer projects: print radio satellite tv video regions: oceania united states topics: biotechSurviving Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: canada: quebec east asia: japan europe: athens barcelona belgium bristol brussels cyprus germany grenoble ireland istanbul lille linksunten nantes netherlands norway portugal united kingdom latin america: argentina cmi brasil rosario oceania: aotearoa united states: austin big muddy binghamton boston chicago columbus la michigan nyc portland rochester saint louis san diego san francisco bay area santa cruz, ca tennessee urbana-champaign worcester west asia: palestine process: fbi/legal updates process & imc docs projects: radio satellite tv |

printable version

- js reader version

- view hidden posts

- tags and related articles

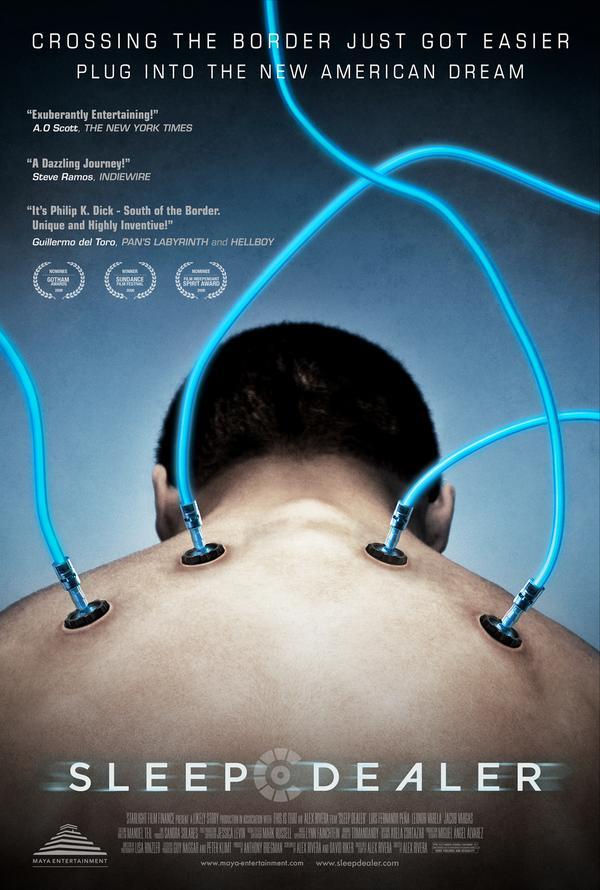

Alex Rivera Discusses His Film Sleep Dealerby RP Wednesday, Apr. 15, 2009 at 7:12 PMTwelve years after its inception, Alex Rivera's first dramatic feature opens in major U.S. cities on Friday April 17 and may spread in ensuing weeks. Last week Rivera took questions from alternative media.

Science fiction seems to work best when it addresses society's “pink elephants.” When Rod Serling was unable to produce certain scripts (including a few based on the then-recent Emmett Till murder), he turned to science fiction, a seemingly harmless genre. Thus, Twilight Zone was born. Gene Roddenberry took a similar approach in the original Star Trek series.

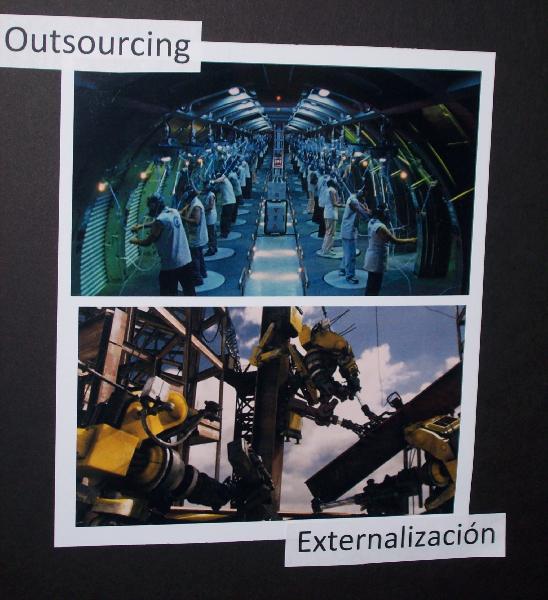

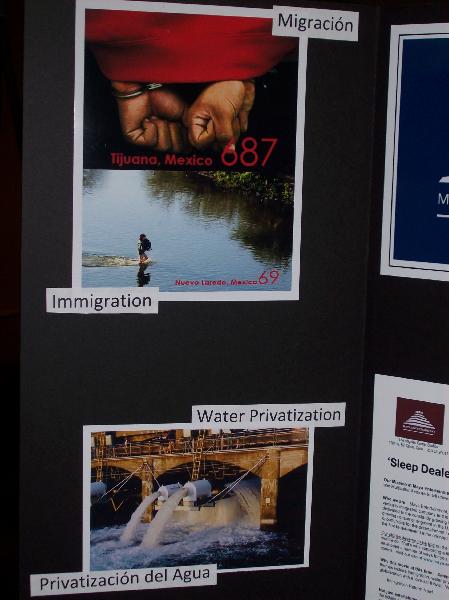

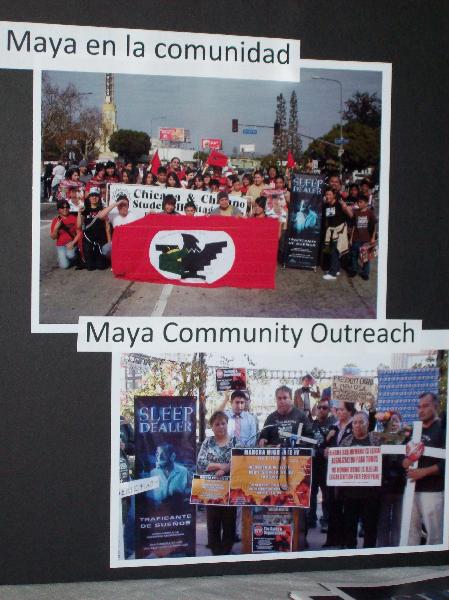

Sadly, an argument could be made that this rarely happens in science fiction films or TV, even when a writer's intentions are good. However, (in this author's opinion) a new filmmaker, Alex Rivera, is effectively using the genre to address globalization, immigration, militarism, and other issues in his movie Sleep Dealer, which opens in major U.S. cities on April 17th (and may spread out in ensuing weeks). The film is set sometime in the future and concerns Memo Cruz (Luis Fernando Pena), whose Oaxacan village is strangled by water privatization and U.S. military intervention via drone airplanes. Memo must find work in the north, but physically entering the U.S. is no longer possible: the border has finally become impenetrable. Instead, he is hooked up to a virtual reality system in Tijuana, where he controls a robot at an American construction site. (Mexican workers manipulate robots at other distant locations, too, including slaughterhouses.) Rivera hopes that Sleep Dealer will start a trend of science fiction movies that address social issues around the world. Recently on KPFK's Voices from the Front Lines (Monday April 13), he suggested that another person's science fiction film could address, say, the seemingly interminable Palestine-Israel conflict. (This interview can be downloaded from KPFK's Audio Archives for the next 90 days, or it can be purchased from the Pacifica Radio Archives. (On opening weekend, a portion of ticket purchases will got to KPFK. Details here. Also, the film's distributor is “offering a 30% Rebate program for community groups to fundraise,” said Laura Palomares of Maya Entertainment. “As an organizer, this was icing on the cake. Our Grassroots Outreach Team has been able to connect over 15 Undocumented Student Groups from College Campuses, dozens of Mexican Federations, churches, schools and non-profits with this great and unique opportunity.” Further information about this is coming soon.) Below is a question-and-answer session with director Alex Rivera, which followed an advance screening of Sleep Dealer on April 9th in Burbank, California. The event was attended by representatives of KPFK's Soul Rebel Radio, Voices from the Front Lines, LA IndyMedia, and others. Interviewer #1: What was your inspiration for the film? Rivera: Well the idea came to me about 10 years ago. In the news I was seeing two things happening: one was the internet was connecting the planet, and there was this talk of a global economy--and at that exact same time they were building a wall between the United States and Mexico. And so I saw the world kind of changing in this ironic way, where it was becoming more connected and more divided at the same time. I come from an immigrant family: my dad came from Latin America to work here in the United States. And I started wondering, “Where is this all going?” and I had this kind of bizarre fantasy about a world where the border was closed, and the workers stayed on the other side of the border and used the internet to cross, so their energy would come to America, but their bodies would stay out. So that's where the idea came from. Interviewer #2: [The questioner, a Oaxacano, mentions that the film's opening takes place in Oaxaca, Mexico, but could tell that it was filmed elsewhere.] Rivera: [A]ctually we didn't didn't film in Oaxaca, we filmed in the desert state of Queretaro in the north. And it [the village within Oaxaca] is a made up place. . . . Santa Ana del Rio is a fantasy village, but we chose the state Oaxaca because of many reasons. When we started the film there hadn't been anything of the conflict in Oaxaca first of all, but I chose it because it seemed like a place where ancient Mexico and the indigenous traditions of Mexico were still very present. The culture of the milpa and this culture that's thousands of years old is there, but it's also right on the edge of migration, it's on the edge of the connection to the north. So it seemed like the right place for the story to start. But I know for a Oaxacano there are many things that don't seem real. Interviewer #3: [Rivera is asked about the futuristic terminology and slang used in the film.] Rivera: Well I think Latinos and people who live in the border region here, we make up words all the time. It's part of what we do. My friends and I are always playing with languages. The first pun that came up for me was Cybracero because I was talking to my friend about this idea [where] if a worker stays in Mexico, but their energy goes to America but their body never does. [I]t's like the Bracero Program: they wanted the work but without the worker. And I said, “Ah yeah, but this would be cyber, the Cybracero Program. And so I came up with the Cybracero Program, and then I was like: “Ah, Cybracero would need somebody to help them cross over. They would need a coyotl or a “coyotek.” And so I just start[ed] to play with the language. And there were bad puns along the way [in the creative process]. The people who didn't like them would call them “netbacks.” [Laughter.] Those bad ones didn't make it into the movie, but part of the creative process was to play with the language. Interviewer #4: I really enjoyed it . . . because [it addresses] globalization, issues about water, politics, indigenous rights, migration. It really speaks to that generation, and it really speaks, I think, to some of the other films on immigration that are equally important and that bring up these issues as well as globalization. But the storyline and the creativity really pulls you in in a way that's very refreshing and very different, so I want to thank you for doing it. Rivera: Well thank you very much. The struggle with the film is to try to make a contribution, I guess, to the history of films about immigration, because El Norte changed my life when I saw that, that really impacted me. And there's been movies like that all the way up to La Misma Luna; Sin Nombre; and Sugar, which is out now. There's been a long history of stories about immigration. What I was trying to do with Sleep Dealer, using science fiction, was to try to find a way [that] we could look at it through the point of view of a family. A family divided by the border—that's true, and that's a big part of the story—but there's another part of the story, too, which is that this is a massive economic, transformative force that is not going to stop. And it might take different shapes in the future, but this dynamic of a country, in this case America, bringing in millions of workers effectively but then pushing them out at the same time: them here but then rejected here, called illegal. It's hard to see the big picture [of this phenomenon] through just one family, and I thought that maybe through science fiction and through exaggerating things and kind of entering the world of fantasy, we could talk about—or imagine—where this is going and what it's about in a more systematic sense. The struggle was to try to find a character and an emotional through line to talk about a systemic, massive phenomenon. [The conversation segues back to Rivera's inspirations for the film.] . . . [When] I grew up I loved Star Wars, I loved Blade Runner. I grew up in America as an American kid but with an immigrant father. My dad came from Peru to the United States to work. So when I see Luke Skywalker I sometimes think of him like an immigrant: his house was blown up by this imperial army, and he had to leave his house and go search for his dreams. But even though in our culture we celebrate someone like Luke Skywalker, nobody asks him for a passport. And when he goes to kind of cross the border, we root for him to break the law, we root for him to escape, but then in our political culture in this country we attack people who are here to pursue their dreams. My dream was to use film to say: “Let's look at people who in our culture are viewed as outsiders--immigrants, workers--and see if I could use science fiction, to use this film to make that person a hero, to say the future belongs to everybody. The future belongs to all of us. The future belongs to Latinos, to Hindus, to African Americans.” The future belongs to everybody, but we don't see that in film. Interviewer #5: I thought politically it was excellent, and I hope that the way you executed it will also make it attractive to audiences that are maybe not too involved. So I'm curious what kind of attention you've gotten or hope to get. Rivera: Well so far it's been really interesting in terms of the attention. Obviously, you guys are here. It's also been covered in Wired magazine, and the New York Times has written about it. It's traveled around the world: we took it to the Berlin Film Festival. . . . But it's all about next Friday. It opens in theaters next Friday, and here in Los Angeles it's on 25 screens. The company that's putting it out, Maya, [believes] that this story can be entertaining and thought-provoking, that it can be Latino and mainstream, and so they're going wide with it. . . . I promise you guys that I make this not to make money, that's for sure, and that I make this not to make money, and I don't make it just for entertainment. All of the films that I've been making for the past 15 years have come from a social commitment and a desire to see a different world and a different cinema. So if we make this one a success, all of us together, I promise you I'll make another one, and it's going to be better [laughs]. Interviewer #1: Lately I've been finding myself getting increasingly scared of robots. A couple months ago on Democracy Now [see: Democracynow.org] they talked about drones and how science fiction authors are now being used to consult with the Pentagon for robotic warfare, and this movie kind of increased that [anxiety]. I even had a nightmare about nanoprobes invading my body. [Laughter.] Rivera: I hope you wrote it down because maybe in 10 years from now you could have the movie of [that]. That's where things start: in nightmares and dreams. Interviewer #1: Or maybe it will be happening in 10 years from now. Rivera: Yeah, but the truth is that right now—maybe even right now—there's drones flying over the U.S.-Mexico border. We live in a world right now where they'll pay $15 million to buy this remote control plane with cameras on it and fly it over the border to hunt for people who are carrying jugs of water through the desert. That's our reality. So it's very hard as a science fiction filmmaker or as a storyteller to imagine anything weirder: the reality that we live in is science fiction. Often when we think about immigration in our storytelling, you still see people wading across the border or images of immigration 20 years ago. Today, whether it's the surveillance on the border, night vision cameras, drones, the X-ray technology that they're using on the border now, all this stuff is like Mad Max or some kind of futuristic nightmare that they want to build, that our tax dollars are going to build, that looks like Blade Runner. So it's not for a joke that I'm mixing science fiction with this issue of immigration. It's because I think immigrants, whether it's at the border in terms of confronting the militarization or it's once you cross over using phone cards, using money wiring services, sending homes videos back and forth, immigrants are users of technology in a way that other families are not. That's been one of the questions I've been looking at from all these different angles. Anyway, more than anything I hope the story was enjoyable. Interviewer #6: [The question and ensuing conversation pertains to the issue of water ownership depicted in the film and the parallels between Bechtel having once privatized the water in Bolivia.] Rivera: You know, that was almost a side echo. . . . It's like a visual and spiritual element but also an expression of this material controlled at the north, this influence the north has always had on Latin America that makes this story of migration a circular one. The idea is that in the village, hope there had already been killed so he [Memo, the protagonist] had to go north. So anyway, you got it. SPOILER ALERT

One of the things that I appreciate the most—there's many things—is that you use [actor] Jacob Vargas really as a Chicano from the U.S., and he's sort of representing himself truly to his people. The aspect that he himself made a major break: he was an oppressor, and [he realized] he was on the wrong side. I just really thought that was a hopeful aspect of the film. The movie's very hopeful in that sense and not just like “Oh my god, what the hell am I going to do?!” I think that is really one of the critical aspects of the film that it is very visionary. Rivera: To me the hope is in the ability to make new alliances . . . and new solidarities that cross borders, that span the globe. If there's ever to be a global labor movement it will be because of technology, but that technology also enables corporations to move their factories and try to avoid a labor movement, that technology also allows the military to do all sorts of nightmarish things. So we live in a moment right now that's a battle over technology. Who will make themselves more powerful? Will it be corporations, militaries, or people who are trying to push back and build a hopeful future? So thank you for recognizing that, and that was what I was hoping came out at the end was this idea of an alliance.

Interviewer #1: I appreciated, too, that there's been a lot of movies about virtual reality, but at some point they tend to start having action and fistfights, but [not in] this movie. There were some shots of the drones flying, but people aren't going to get into it like it's a video game or a simulator ride. I think the upcoming Star Trek movie looks like a two-hour simulator ride. Rivera: Thanks a lot. I didn't have enough budget for fistfights or enough budget for action scenes, [laughter] so all I had was my ideas, so that's what the film drives on mostly. And that's what I've always loved about science fiction: the ideas. Interviewer #1: We don't see much of that in the science fiction movies. Rivera: Usually in the science fiction movies you get a title card at the beginning that tells you all the ideas, and then after that they have to start killing each other. [Laughter.] In this one I wanted it to be kind of like an onion where it has one layer of the future, and then you peel it, and then you see more of the future, and more of it, and more of it. And through the whole film you're learning aspects of this world as my character travels through it. Part of the thrill of the film, I hope, is an intellectual thrill . . . Interviewer #1: In this film there are explosions, but they're tragic. Whereas in a lot of science fiction movies [the explosions] are like Fourth of July fireworks. [In this film] his house is blown up. Rivera: Thank you, yeah. [The subject segues to how quickly science fiction has been catching up with reality, in this case remote warfare.] It's amazing to me how things that five years ago would seem surreal, or would seem like it should be in a movie and be bizarre or disgusting, or things that were in a movie called Terminator--this idea of robot warfare--that used to be science fiction, and now there it is in the news, not even on the front page anymore. We become so accustomed to it, but I'm hoping this movie makes some of those things ugly and bizarre again and that we can talk about it.

Report this post as:

Alex Rivera discussing Sleep Dealerby RP Wednesday, Apr. 15, 2009 at 7:12 PM

error

Report this post as:

One of the issues addressed in Sleep Dealerby RP Wednesday, Apr. 15, 2009 at 7:12 PM

error

Report this post as:

One of the issues addressed in Sleep Dealerby RP Wednesday, Apr. 15, 2009 at 7:12 PM

error

Report this post as:

More of the issues addressed in Sleep Dealerby RP Wednesday, Apr. 15, 2009 at 7:12 PM

error

Report this post as:

Maya Entertainment community outreachby RP Wednesday, Apr. 15, 2009 at 7:12 PM

error

Report this post as:

|