california_historic_buffalo_soldier_trail.jpg, image/jpeg, 712x534

2019 Veterans Day Weekend, Colonel Charles Young will be honored at the entrance to Sequoia National Park

california_historic_buffalo_soldier_trail.jpg, image/jpeg, 712x534

Charles Young was born into slavery in a two-room log cabin in Mays Lick, Ky., on March 12, 1864. His father Gabriel later fled to freedom and in 1865 enlisted as a private in the 5th Regiment, U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.

His father’s enhanced status as a “Grand Army man” impressed Charles as he grew up in Ripley, Ohio. The son was sent to an all-black elementary school, but he was able to attend Ripley’s integrated high school and graduated at the top of his class in 1881.

Two years later, at the urging of his father, he took the West Point entrance examination. Twenty-year-old Young scored well, received the required nomination from Ohio’s 12th District Congressman Alphonso Hart and reported to the U.S. Military Academy in June 1884. He was the ninth black American admitted to West Point; he would be the third to graduate with a commission as a second lieutenant.

Young had a miserable time at West Point. Charles Rhodes, a white cadet in Young’s class, remembered him as “a rather awkward, overgrown lad, large-boned and robust in physique, and of a nervous, impulsive temperament.” Rhodes recalled that Young’s “life was lonesome” at West Point––hardly a surprise, as most white cadets refused to associate with blacks and subjected them to racial slurs, cruel slights and hostile treatment beyond the normal hazing.

Young considered quitting West Point after his first year, but his father convinced him to stay—though it took Young five years to complete the curriculum. He had difficulty with engineering but excelled in languages, gaining a working knowledge of Latin, Greek, French, Spanish and German. His decision to persevere was a source of pride for him, and he accepted that “duty, honor, country” must be the foundation of his life as an officer. But Young later advised a young black man interested in attending West Point that he could expect “a dog’s life there.”

Young graduated last in his 49-member class in 1889, and from 1894 until 1936 he was the lone black West Point graduate in the Army.

Assigned to the predominantly black 9th U.S. Cavalry (aka “Buffalo Soldiers”), Young served in Nebraska and Utah in the early 1890s before reporting to Wilberforce University, near Dayton, Ohio, as professor of military science and tactics. While at Wilberforce, Young befriended W.E.B. Du Bois, a classics professor who would become one of the leading black American intellectuals of the early 20th century. After leaving Wilberforce, Du Bois and Young continued to correspond, and Du Bois considered Young one of the “talented tenth”—those individuals whom Du Bois and other prominent black intellectuals believed would lead the struggle for racial justice in America.

Young’s patience, discipline and hard work paid off when the United States declared war on Spain in April 1898. On May 13 of that year Ohio Governor Asa S. Bushnell appointed 1st Lt. Young a brevet major in command of the 9th Battalion Ohio Volunteers, an all-black unit. While the major and his men remained stateside, Young gained valuable command experience.

At war’s end Young returned briefly to Wilberforce University before rejoining the 9th Cavalry at Fort Duchesne, Utah. While in command of I Troop, 1st Lt. Young (he had reverted to his permanent rank) learned that one of his men, Sgt. Maj. Benjamin O. Davis, wanted to apply for a commission. Young tutored Davis for the competitive examination and wrote a glowing letter of recommendation. In early 1901 Davis passed the test and was commissioned a second lieutenant. He never forgot Young’s help, particularly after becoming the first black American to reach the rank of general.

In February 1901 Young was promoted to captain in the Regular Army—another first for a black man. Two months later Young and I Troop sailed for the Philippines with the rest of the 9th Cavalry. Stationed on Samar, Young and his men fought the Filipino insurrectos in the jungles of the island’s rugged interior. During one operation Young was leading a scouting party when it came under attack. “Captain Young had fired his revolver so fast,” a corporal later recalled, “that the sight was blown off.” Young then took another officer’s pistol and kept firing at the enemy until reinforcements arrived. Such instances of combat leadership earned Young the moniker “Follow Me” from his men, who vowed they would give their lives for him. The 9th Cavalry returned stateside in late 1902.

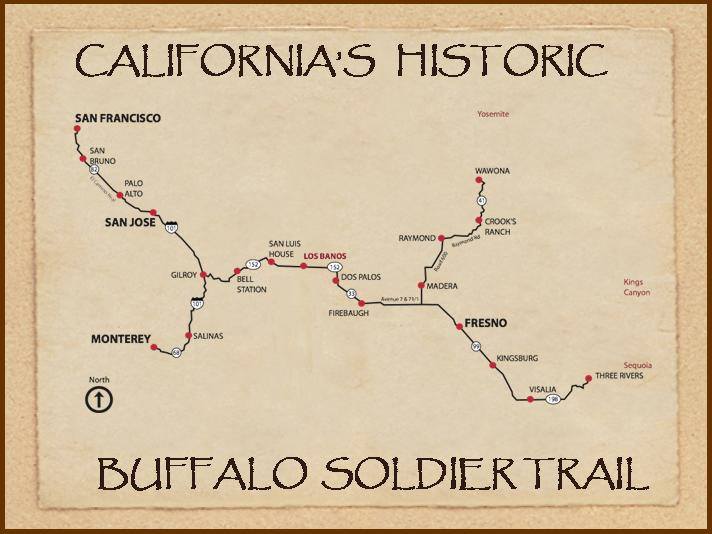

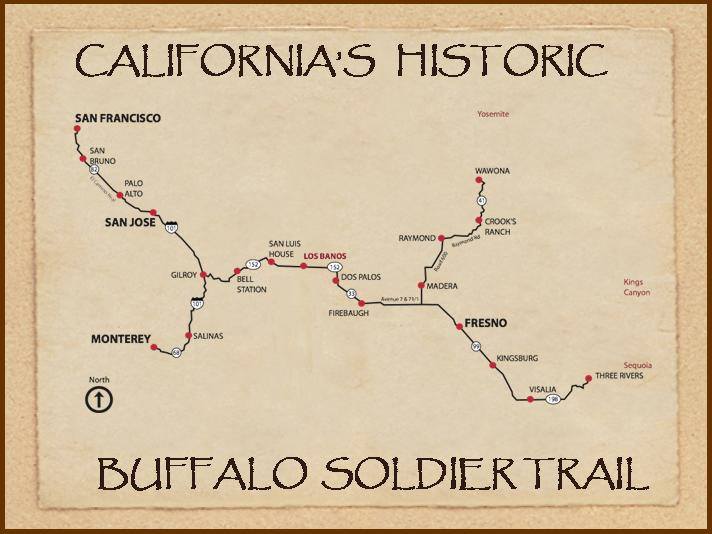

In May 1903, 39-year-old Captain Young, three other officers and 93 enlisted soldiers left the Presidio of San Francisco for Sequoia and General Grant national parks in north-central California. In the years before the 1916 creation of the National Park Service, the Army ran America’s national parks. The War Department detailed junior officers to the Department of the Interior to serve as acting superintendents during the summer. These assignments were always short-lived; the officers never served for more than two consecutive seasons. Consequently, little was expected.

But Young threw himself into his new job. He took charge of the payroll accounts and directed the activities of the park rangers. He stopped the illegal grazing of sheep in the park’s meadows. Young had his men dig firebreaks and place fences around the giant sequoias to protect them from root damage.

The men also began work on a major project: completing a road to the Giant Forest, the park’s major attraction. Civilian crews had completed two-thirds of the road during the past few seasons. Young and his troopers finished it in two months and added another two miles to the road, going on to complete an unfinished road to the town of Visalia, seven miles farther west.

Original: US Army First Black Colonel Honored at Sequoia National Park Entrance