| About Us | Contact Us | Calendar | Publish | RSS |

|---|

|

Features • latest news • best of news • syndication • commentary Feature Categories IMC Network:

Original Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: ambazonia canarias estrecho / madiaq kenya nigeria south africa canada: hamilton london, ontario maritimes montreal ontario ottawa quebec thunder bay vancouver victoria windsor winnipeg east asia: burma jakarta japan korea manila qc europe: abruzzo alacant andorra antwerpen armenia athens austria barcelona belarus belgium belgrade bristol brussels bulgaria calabria croatia cyprus emilia-romagna estrecho / madiaq euskal herria galiza germany grenoble hungary ireland istanbul italy la plana liege liguria lille linksunten lombardia london madrid malta marseille nantes napoli netherlands nice northern england norway oost-vlaanderen paris/Île-de-france patras piemonte poland portugal roma romania russia saint-petersburg scotland sverige switzerland thessaloniki torun toscana toulouse ukraine united kingdom valencia latin america: argentina bolivia chiapas chile chile sur cmi brasil colombia ecuador mexico peru puerto rico qollasuyu rosario santiago tijuana uruguay valparaiso venezuela venezuela oceania: adelaide aotearoa brisbane burma darwin jakarta manila melbourne perth qc sydney south asia: india mumbai united states: arizona arkansas asheville atlanta austin baltimore big muddy binghamton boston buffalo charlottesville chicago cleveland colorado columbus dc hawaii houston hudson mohawk kansas city la madison maine miami michigan milwaukee minneapolis/st. paul new hampshire new jersey new mexico new orleans north carolina north texas nyc oklahoma philadelphia pittsburgh portland richmond rochester rogue valley saint louis san diego san francisco san francisco bay area santa barbara santa cruz, ca sarasota seattle tampa bay tennessee urbana-champaign vermont western mass worcester west asia: armenia beirut israel palestine process: fbi/legal updates mailing lists process & imc docs tech volunteer projects: print radio satellite tv video regions: oceania united states topics: biotechSurviving Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: canada: quebec east asia: japan europe: athens barcelona belgium bristol brussels cyprus germany grenoble ireland istanbul lille linksunten nantes netherlands norway portugal united kingdom latin america: argentina cmi brasil rosario oceania: aotearoa united states: austin big muddy binghamton boston chicago columbus la michigan nyc portland rochester saint louis san diego san francisco bay area santa cruz, ca tennessee urbana-champaign worcester west asia: palestine process: fbi/legal updates process & imc docs projects: radio satellite tv |

printable version

- js reader version

- view hidden posts

- tags and related articles

Isabel Avila's "Parallel Worlds" at the Vincent Price Art Museumby Ross Plesset Sunday, Nov. 18, 2012 at 11:10 AMIn her first solo exhibit, photographer (and contributor to LA IndyMedia) Isabel Avila explores the dual identities of Native American and Mexican American cultures, emphasizing people active in their communities. Avila's photographs, taken over the last few years, are complimented by video discussions, many featuring her photo subjects but also additional people, including Gloria Arellanes, one of the early Brown Berets and member of the Tongva community. (Excerpts of these dialogs can be found further down in this article.) The free exhibit is currently at the Vincent Price Museum through December 8. It will then then relocate to Rancho Cucamonga's Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art and run from January 22 – March 16, 2013. (Location details within the article.)

(Pictured above: Cahuilla Red Elk, Lakota-Cahuilla Agua Caliente Band.)

In her first solo exhibit, photographer (and contributor to LA IndyMedia) Isabel Avila explores the dual identities of Native American and Mexican American omega seamaster replica watches cultures, emphasizing people active in their communities. Avila's photographs, taken over the last few years, are complimented by video discussions, many featuring her photo subjects but also additional people, including Gloria Arellanes, one of the early Brown Berets and member of the Tongva community. (Excerpts of these dialogs can be found further down in this article.) "Through video dialogue and portraiture, the museum goers are not just given facts to go away with but are also left to make their own connections with this subject matter in their own lives," Avila explained. She added, in regards to her photographs, that “these are large scale color photographs, and I'm a photographer that still uses medium format film and shoots with a Hasselblad. “. . . I'm also cooperating with my subjects in these portraits, and the videos bring the subjects to life by including not only what they look like but how they think and feel about issues which is a method for presenting my work from a perspective of Indigenous subjectivity not objectivity.” The free exhibit is currently at the Vincent Price Museum (HOY Space, third floor, on the campus of East LA Community College) through December 8. More here. It will then then relocate to Rancho Cucamonga's Wignall Museum of Contemporary Art (as part of a larger exhibition called The New World. See: http://www.chaffey.edu/wignall/exhibitions.shtml) and run from January 22 – March 16, 2013. A few of Avila's photographic subjects include: *Cahuilla Red Elk (Lakota-Cahuilla Agua Caliente Band), attorney for The Center of Human Rights & American Indian Law (retired) and a member of AIM (American Indian Movement), Los Angeles Chapter, during the Wounded Knee Occupation. *Alfred Cruz, Sr. (Acjachemen), who is pictured at an awareness-building demonstration (which occurs almost every month), concerning the threatened sacred site at Bolsa Chica in Huntington Beach. More about the site in this short 2009 video. As described in the exhibit: *Noel Vargas Hernandez, a Oaxacan artist from an indigenous Zapotec village, whose print work has appeared at Self Help Graphics. *Maynor, a day laborer from Honduras. Originally an engineer, he was forced to leave his family and migrate to the U.S. due to lack of jobs. He is trying to earn enough money to return home. Below are transcript excerpts of the video interviews. Virginia Carmelo “My name is Virginia Carmelo, I am a Gabrielino-Tongva. Those are the original peoples from the Los Angeles area. I'm a former tribal chairperson, I'm a mother of six adult children, and grandmother to seven grandchildren. When I was in college I became involved with MEChA on the campus that I went to, which was Cal State Fullerton. One of the gucci replica watches things that we did initially was go out and recruit, from the 22 Orange County barrios, students to come into the EOP [Educational Opportunity Program]. We also became involved in different events that were happening in the community. We had a community center right here which I now work at. It's been here since that time, the early '70s. It is a direct result of the Chicano Movement—people got together, neighbors got together and wanted a community center. We were supported by MEChistAs from Cal State Fullerton and community members. It's gone through some changes, but it's still there serving the community. “In the Chicano communities we were trying to get away from 'Mexican' because we really didn't really identify with Mexican. Mexican was somebody who's from Mexico, and none of us were, even though we sometimes had great grandparents or grandparents from Mexico. “We wanted the rights and the abilities to, for instance, take advantage of education like other people. “So we realized that we were a product of different cultures. Along with that went the concept of being native to the lands, in other words, not being foreign as were the people who established this country 200 years ago. I was even more conscious of that because I wasn't from someplace else. My family was always from the areas around here [Orange County], areas near the rivers.” Gloria Arellanes “I have been an activist since the late '60s to the present. I started in the Chicano Movement, and presently I am an elder and grandmother of the Gabrielino-Tongva tribe, the local tribe to Los Angeles. “I stayed away [from the Chicano/a Movement] for 20 years. I was called back to a Moratorium meeting; I went to that reunion. I love seeing people from the past. It was really, really nice. And then I got called [in] the next 20 years for the commemorative with Rosalio [Munoz]. He actually helped me to accept my own personal history. I was denying it all this time, not denying it but saying, 'I don't want to be a part of it; I'm different; I'm in the Tongva community now; I am a Native woman; I am an elder; I go to these grandmother gatherings, and I'm recognized internationally now with other grandmothers; and I know my culture; I'm learning my language; I have my regalia. This is me now.' But in all the beauty of that—and I love my Tongva culture(1)--when I go back to the Chicano community, I miss that community and the people that I had worked with. So I am not so easy to say: 'No, no, I am not part of that. No, no, that was way back then.' I now say, 'Yes, that is my history, that is part of me.' I can't deny that. “. . . So I'm starting to feel more comfortable going with the Chicano community. In fact, Rosalio took a picture of four of us Brown Berets from way back then, and he [labeled it] 'Gloria Arellanes – Chicana, Tongva, grandmother, elder.' He used those words. And somebody else recently referred to me as a Chicana-Tongva, and I'm comfortable with that. I'm comfortable in the fact that I can go to the Chicano community and relate. “. . . All the things we fought for, all the things that people got arrested for, got beaten up for, some people even died for what they believed in—it's all coming back again. They're losing their education, it's getting to where you won't be able to afford it; health issues are bad; housing is bad. Everything that we fought for has been undone. “It's a different time: we're seeing more diversity in the community. There's Salvadorans, there's different people from different [areas]. “I'm seeing this transition--where it was Chicanos, I'm seeing that people are now going back to their indigenous roots, and they're practicing their traditional form of religion and prayer. “ (Arellanes adds that she sees a strong need for dialog in the brown community regarding Aztlan and other cultures, including her own Tongva.) Cahuilla Red Elk “If you're going to be involved in activism, you have to make sure that your spirituality and that your point of reference is always to our ancestors. They are the ones who initiated the practice for us. That's the stronghold. It's very, very simple, and it's very clear, but the hard part is doing the balance in the two worlds. There can be and there are other methods on how to present issues without the cost of having to be caught up in the institutions, in the prisons, and in the courts, and with people and governments whose agenda is to remove us, do away with us. “The method that has to be used is a collective effort, that we have to go together as the Indian Nation --not Indian Nations. We already tried Indian Nations—we have to go as one nation, as indigenous people. “. . . I would like to see history be part of integrity, of how it presents itself, of how people tell stories. I was just in a place a couple days ago, and in this museum there was all these explanations about all these cultures or religious groups that were being attacked or had been attacked, but there was nothing about my people. And in the very place where the building sat, I know a story about: “I know a story that my people from the desert came to Los Angeles—it was a hub, a trade center. We would go out to the ocean and trade our goods with the people at what now is known as Catalina. All the people would come together. Why did they come to this particular region, to Los Angeles? Well, L.A. And this particular area here is one of the meridians of migration for the eagle, not particularly L.A. or downtown L.A., but it's one of the meridians. The Meridians look like a hand: they come from the north, and they go this way, and this way, and this way... [uses as visual reference her hand and fingers]. Santa Barbara is known as the Western Gate. If you talk to any person that's from that region, from Santa Ynez Reservation, they'll tell you: that's the Western Gate. And then you have the L.A. Area, and then you have the Laguna area, and you have [the meridian] down by Doheny, and then you have another meridian which is the Gulf of Mexico. . . . And these are where the eagles go. . . . and our people knew this instinctively. I come from the Bird People here in California. “So they watched all of these signs. We've lived by watching the signs. We didn't have newspapers--we communicated through trading baskets and pottery.” ----- (1)On the subject of the Tongva, Arellanes further commented: “and I'm part of the Ti'at Society, and we're a maritime culture, and we have a canoe, and we haven't crossed the ocean yet, but we've gone around Catalina. Four of those Channel Islands were our lands. David Sanchez and the Brown Berets reclaimed it [Catalina] for Mexico—no, it is Tongva land. We called it Pimu. That's were we would wait for the redwoods to wash down the ocean, and we built our ti'ats with them. We've re-enacted it—it hasn't been done in over 200 years. The culture is just absolutely beautiful.”

Report this post as:

Alfred Cruz protesting development on a sacred siteby Ross Plesset Sunday, Nov. 18, 2012 at 11:10 AM

There is a demonstration at Bolsa Chica in Huntington Beach almost every month. This short video, made in 2009, describes the site: http://www.youtube.com/watch?playnext=1&v=UjA8PI9Nx4g&list=TLbSh9n Photo by Isabel Avila.

Report this post as:

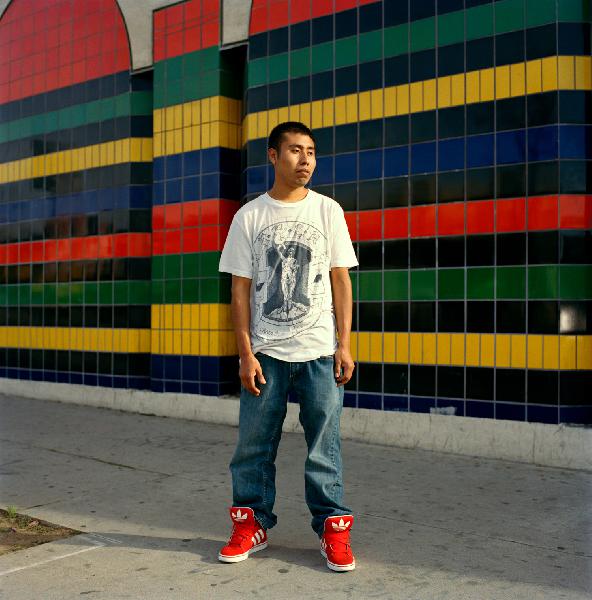

Noel Vargas Hernandez (Oaxacan artist)by Ross Plesset Sunday, Nov. 18, 2012 at 11:10 AM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

Report this post as:

Part of the gallery and displaysby Ross Plesset Sunday, Nov. 18, 2012 at 11:10 AM

error

Report this post as:

Exhibit: Parallel Worldsby Ross Plesset Sunday, Nov. 18, 2012 at 11:10 AM

The closest picture is of Virginia Carmelo, a Gabrielino-Tongva, grandmother, and long-time activist.

Report this post as:

Parallel Worlds by Isabel Avilaby Ross Plesset Sunday, Nov. 18, 2012 at 11:10 AM

At left: One of the video presentations. This one features Lazaro Arvizu, Jr., son of Virginia Carmelo and a renowned artist of the same name. Right: A picture of shell middens at the endangered sacred site Bolsa Chica in Huntington Beach

Report this post as:

|