| About Us | Contact Us | Calendar | Publish | RSS |

|---|

|

Features • latest news • best of news • syndication • commentary Feature Categories IMC Network:

Original Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: ambazonia canarias estrecho / madiaq kenya nigeria south africa canada: hamilton london, ontario maritimes montreal ontario ottawa quebec thunder bay vancouver victoria windsor winnipeg east asia: burma jakarta japan korea manila qc europe: abruzzo alacant andorra antwerpen armenia athens austria barcelona belarus belgium belgrade bristol brussels bulgaria calabria croatia cyprus emilia-romagna estrecho / madiaq euskal herria galiza germany grenoble hungary ireland istanbul italy la plana liege liguria lille linksunten lombardia london madrid malta marseille nantes napoli netherlands nice northern england norway oost-vlaanderen paris/Île-de-france patras piemonte poland portugal roma romania russia saint-petersburg scotland sverige switzerland thessaloniki torun toscana toulouse ukraine united kingdom valencia latin america: argentina bolivia chiapas chile chile sur cmi brasil colombia ecuador mexico peru puerto rico qollasuyu rosario santiago tijuana uruguay valparaiso venezuela venezuela oceania: adelaide aotearoa brisbane burma darwin jakarta manila melbourne perth qc sydney south asia: india mumbai united states: arizona arkansas asheville atlanta austin baltimore big muddy binghamton boston buffalo charlottesville chicago cleveland colorado columbus dc hawaii houston hudson mohawk kansas city la madison maine miami michigan milwaukee minneapolis/st. paul new hampshire new jersey new mexico new orleans north carolina north texas nyc oklahoma philadelphia pittsburgh portland richmond rochester rogue valley saint louis san diego san francisco san francisco bay area santa barbara santa cruz, ca sarasota seattle tampa bay tennessee urbana-champaign vermont western mass worcester west asia: armenia beirut israel palestine process: fbi/legal updates mailing lists process & imc docs tech volunteer projects: print radio satellite tv video regions: oceania united states topics: biotechSurviving Citieswww.indymedia.org africa: canada: quebec east asia: japan europe: athens barcelona belgium bristol brussels cyprus germany grenoble ireland istanbul lille linksunten nantes netherlands norway portugal united kingdom latin america: argentina cmi brasil rosario oceania: aotearoa united states: austin big muddy binghamton boston chicago columbus la michigan nyc portland rochester saint louis san diego san francisco bay area santa cruz, ca tennessee urbana-champaign worcester west asia: palestine process: fbi/legal updates process & imc docs projects: radio satellite tv |

printable version

- js reader version

- view hidden posts

- tags and related articles

San Pedro: Science Center Endangered/Tongva Village Site Revitalizationby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PMJacob Gutierrez, a Tongva, is trying to preserve two valuable Indigenous and environmental areas in San Pedro.

Jacob Gutierrez, a Tongva, has a lot on his plate right now. The last science center in the LA Unified School District is “on the chopping block” due to budget cuts in education. (LAUSD originally had six.) This facility has been a resource for everyone, especially children. Just up the street is the site of Shwaanga (Ken Malloy Regional Park), one of the largest Tongva villages in pre-Spanish times, a site which has been suffering from pollution in recent centuries.

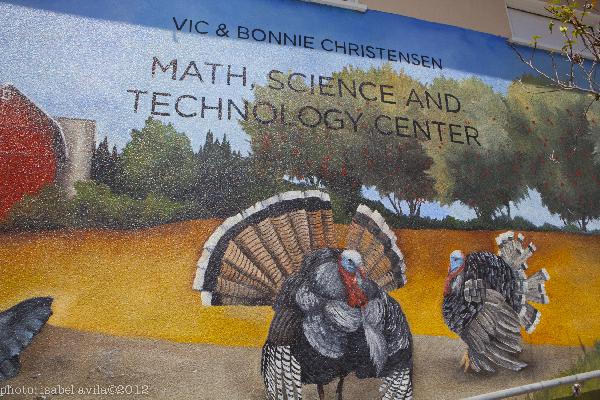

The San Pedro Science Center on Barrywood Avenue contains several gardens, consisting of over 80 native plants and fruit trees. Native wildlife is drawn there, including blue butterflies. There are also over 150 animals that children can visit, all rescues. Oftentimes they have been confiscated by the U.S. Government at the southern border and would have been killed were it not for the Center. A 34-year-old pony (now retired from being a ride vehicle) would now be glue, Jacob said. There is also Ophelia, an enormous pig (pictured here); a turkey; chickens; goats; geese; and numerous reptiles. Children who have visited this place have also been able to learn about Indigenous people and their ways. It is also here, in a classroom, that Jacob and UCLA Professor/Mentor Pam Munro work to keep the Tongva language alive(1). Unfortunately, the School Board can no longer afford to pay operating expenses for the Center, and field trips have become a luxury for schools. According to Jacob, it costs $400 for a bus and another $200 for a substitute to fill in for the teacher overseeing a trip. A group called Keepers of Indigenous Ways (KIW), which Jacob represents, has been working with the Science Center to keep it open in this era of austerity for the majority. The facility is open to “volunteers, friends & families” on the first Saturday of each month. Just up the street is a much bigger undertaking for Jacob, the site of what was a huge gathering place for Indigenous people, the village of Shwaanga(2)—a site which needs a lot of work. Today the space is used for activities such as camping, picnics, and bird-watching, but in pre-European times, people would travel by boat from islands including Pimu (Catalina Island) and numerous inland communities via canoelike boats plying rivers, as well as different parts of the California coast. “Shwaanga was one of the densest populated Tongva villages of the Los Angeles Basin,” Jacob said, “a gateway to the ocean and to the interior.” Shwaanga was also “a Pivotal place for trade, hunting, fishing, a place for gatherings, festival,s and a place to collect and drink fresh water once called 'Paayaxche-Sweet Water,' now called Machado Lake. In fact, our coveted soapstone from Catalina Island has been found in places like Oklahoma.” The site, which is still quite beautiful, has unfortunately suffered from chronic vandalism and pollution in recent centuries. A proposed restoration, which has received serious attention, would secure the premises at night via fencing--right now it is vulnerable literally every night--facilitate its traditional use as a gathering and cultural area, educate both Natives and non-Natives, and detoxify the water. The above-mentioned Machado Lake comprises much of Shwaanga and attracts native birds--over 350 species including egrets have been sighted--however, the water is very polluted. Dissected birds have been found to be full of worms. Other local birds, found to have deformities, used to be taken in by the Science Center until the LAUSD began to object. “It's a slew, like a swamp,” Jacob said of the lake. “There's probably cars and bodies and everything you can think of that's been thrown in there since the Europeans got here. You've probably got fish in there with three eyes. You do not want to eat or drink anything out of there. “What they're going to do is take a section at a time and drain it. There are three or four sections. They're going to use a big, giant vacuum cleaner [laughs], and it's going to go into this big trash bag like 10' x 20'. They fill those up with all the sludge and the mud, and everything, but the water seeps out . So it becomes hard like a brick, and then a truck picks it up and takes it away. The very top layer of the stuff is going to be totally toxic. Some of the sludge might be okay to use as fill dirt. They have biologists who will be working with them every step of the way [to determine] the condition of that water.” Jacob's ideal scenario for a revitalized Shwaanga would be a passive park; however, multi-use is more likely, with activities such as hiking, biking, and camping. The Tongva could use natural materials on-site to build a village (including sweat lodges), tule canoes to ply the lake, and baskets. Jacob added that since the Tongva language is tied to the land, Shwaanga would be an ideal place for youths to learn it from elders. However, this facility would also be an opportunity for non-Natives to learn about Tongva. Jacob described this scenario (and a beautiful rendering by him can be seen here): • Imagine spending an entire day with real Native Americans, doing things that they have been doing for thousands years. Indigenous Ways hold significant California Cultural history. Indigenous Plants - Conservation and Ecology Indigenous Animals - Wild Life Education Indigenous People- Language/ Culture/ History Programs that will describe the historical and current ecological relationships between the natural resources and Indigenous interaction with the wetlands, water and air we breath. Other proposed features include an Earthship home that would be built by children and a berm to act as a sound barrier from passing traffic on the side near Anaheim Street and obscure an unsightly ConocoPhillips facility nearby. Restoring the lake and surrounding land (as well as campground restoration) would cost $117,000,000. ($750,000 in Quinby funds will be used.) The cost of a fence and security patrols to prevent further vandalism has not yet been ascertained. Jacob mentioned a major political hurdle for this endeavor: the ever-changing makeup of local political bodies. Once allies are made, they tend to not stay around. However, an exception is former City CouncilWoman Janice Hahn, who was—and remains-- a big supporter and is now in the U.S. Congress. “It's a lot of coordination,” he remarked of this major undertaking. “I don't know if I'll see it in my lifetime.” ----- (1)Jacob said the Tongva language would be gone now had it not been for the work of John P. Harrington, who visited villages in the early 20th century and wrote down words on anything he could find. In all, he compiled 6,000 pages of notes, which Jacob coded. (More about Harrington here.) In recent years, the emphasis of Jacob's courses has been on learning grammar. (2)In William McCawley's book The First Angelinos, this place name is said to mean “junco [tule]. There was lots of junco about the village.” The quote is attributed to Jose Zalvidea, an Indigenous consultant to linguist-researcher John P. Harrington from 1914 to 1917. The quote is on page 66 of “Angelinos.”

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

A boat from an indigenous group in Polynesia. Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Rescued animals at the San Pedro Science Center. Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Rescued turkey at the San Pedro Science Center. Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Another rescued animals at the San Pedro Science Center. Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

The San Pedro Science Centerby R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by Isabel Avila.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

Site of Shwaanga (Ken Malloy Regional Park)by R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Machado Lake, which is in dire need of restoration due to pollution. Originally, Shwaanga was surrounded by wetlands and clean water. Photo by R. Plesset.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

Site of Shwaanga (Ken Malloy Regional Park)by R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Egrets at Machado Lake. Local birds are attracted to the lake, but unfortunately, the water is toxic. Photo by R. Plesset.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

Site of Shwaanga (Ken Malloy Regional Park)by R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

A bridge crossing over part of Machado Lake. Photo by R. Plesset.

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

Site of Shwaanga (Ken Malloy Regional Park)by R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

Photo by R. Plesset

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

Site of Shwaanga (Ken Malloy Regional Park)by R. Plesset, Sci Center photos: Isabel Avila Saturday, Jun. 02, 2012 at 12:46 PM

An example of the vandalism at Shwaanga (Ken Malloy Regional Park) and the need for fencing and patrols. Photo by R. Plesset

keepersofindigenousways.org/id19.html

Report this post as:

|