by Armando Liwanag

Wednesday, Sep. 14, 2011 at 6:45 PM

Revisionism is the systematic revision of and deviation from

Marxism, the basic revolutionary principles of the proletariat

laid down by Marx and Engels and further developed by the series

of thinkers and leaders in socialist revolution and construction.

The revisionists call themselves Marxists, even claim to make an

updated and creative application of Marxism but they do so

essentially to sugarcoat the bourgeois antiproletarian and

anti-Marxist ideas that they propagate.

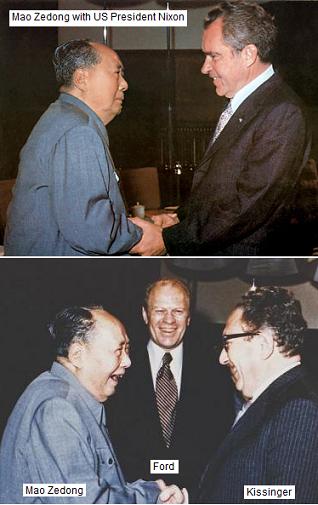

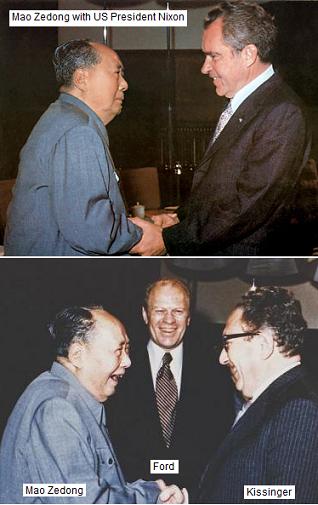

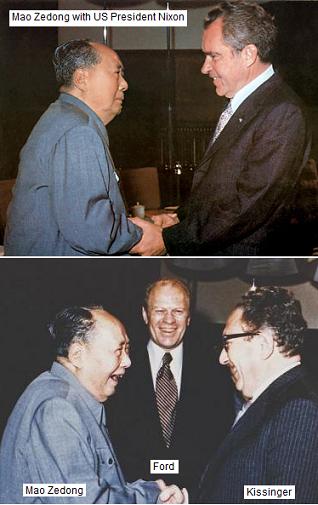

1975-mao-nixon-mao-zedong-ford-kissinger-cpp-ndfp.jpgcbwqre.jpg, image/jpeg, 318x505

The classical revisionists who dominated the Second International

in 1912 were in social-democratic parties that acted as tails to

bourgeois regimes and supported the war budgets of the capitalist

countries in Europe. They denied the revolutionary essence of

Marxism and the necessity of proletarian dictatorship, engaged in

bourgeois reformism and social pacifism and supported colonialism

and modern imperialism. Lenin stood firmly against the classical

revisionists, defended Marxism and led the Bolsheviks in

establishing the first socialist state in 1917.

The modern revisionists were in the ruling communist parties in

the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. They systematically revised

the basic principles of Marxism-Leninism by denying the

continuing existence of exploiting classes and class struggle and

the proletarian character of the party and the state in socialist

society. And they proceeded to destroy the proletarian party and

the socialist state from within. They masqueraded as communists

even as they gave up Marxist-Leninist principles. They attacked

Stalin in order to replace the principles of Lenin with the

discredited fallacies of his social democratic opponents and

claimed to make a "creative application" of Marxism-Leninism.

The total collapse of the revisionist ruling parties and regimes

in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, has made it so much

easier than before for Marxist-Leninists to sum up the emergence

and development of socialism and the peaceful evolution of

socialism into capitalism through modern revisionism. It is

necessary to trace the entire historical trajectory and draw the

correct lessons in the face of the ceaseless efforts of the

detractors of Marxism-Leninism to sow ideological and political

confusion within the ranks of the revolutionary movement.

Among the most common lines of attack are the following:

"genuine" socialism never came into existence; if socialism ever

existed, it was afflicted with or distorted by the "curse" of

"Stalinism", which could never be exorcised by his anti-Stalin

successors and therefore Stalin was responsible even for the

anti-Stalin regimes after his death; and socialism existed up to

1989 or 1991 and was never overpowered by modern revisionism

before then or that modern revisionism never existed and it was

an irremediably "flawed" socialism that fell in 1989-1991.

There are, of course, continuities as well as discontinuities

from the Stalin to the post-Stalin periods. But social science

demands that a leader be held responsible mainly for the period

of his leadership. The main responsibility of Gorbachov for his

own period of leadership should not be shifted to Stalin just as

that of Marcos, for example, cannot be shifted to Quezon. It is

necessary to trace the continuities between the Stalin and the

post-Stalin regimes. And it is also necessary to recognize the

discontinuities, especially because the post-Stalin regimes were

anti-Stalin in character. In the face of the efforts of the

imperialists, the revisionists and the unremoulded petty

bourgeois to explain everything in anti-Stalin terms and to

condemn the essential principles and the entire lot of

Marxism-Leninism, there is a strong reason and necessity to

recognize the sharp differences between the Stalin and

post-Stalin regimes. The phenomenon of modern revisionism

deserves attention, if we are to explain the blatant restoration

of capitalism and bourgeois dictatorship in 1989-91.

After his death, the positive achievements of Stalin (such as the

socialist construction, the defense of the Soviet Union, the high

rate of growth of the Soviet economy, the social guarantees,

etc.) continued for a considerable while. So were his errors

continued and exaggerated by his successors up to the point of

discontinuing socialism. We refer to the denial of the existence

and the resurgence of the exploiting classes and class struggle

in Soviet society; and the unhindered propagation of the

petty-bourgeois mode of thinking and the growth of the

bureaucratism of the monopoly bureaucrat bourgeoisie in command

of the great mass of petty-bourgeois bureaucrats.

From the Khrushchov period through the long Brezhnev period to

the Gorbachov period, the dominant revisionist idea was that the

working class had achieved its historic tasks and that it was

time for the Soviet leaders and experts in the state and ruling

party to depart from the proletarian stand. The ghost of Stalin

was blamed for bureaucratism and other ills. But in fact, the

modern revisionists promoted these on their own account and in

the interest of a growing bureaucratic bourgeoisie. The general

run of new intelligentsia and bureaucrats was petty

bourgeois-minded and provided the social base for the monopoly

bureaucrat bourgeoisie. In the face of the collapse of the

revisionist ruling parties and regimes, there is in fact cause

for the Party to celebrate the vindication of its

Marxist-Leninist, antirevisionist line. The correctness of this

line is confirmed by the total bankruptcy and collapse of the

revisionist ruling parties, especially the Communist Party of the

Soviet Union, the chief disseminator of modern revisionism on a

world scale since 1956. It is clearly proven that the modern

revisionist line means the disguised restoration of capitalism

over a long period of time and ultimately leads to the

undisguised restoration of capitalism and bourgeois dictatorship.

The supraclass sloganeering of the petty bourgeoisie has been the

sugarcoating for the antiproletarian ideas of the big bourgeoisie

in the Soviet state and party.

In the Philippines, the political group that is most embarrassed,

discredited and orphaned by the collapse of the revisionist

ruling parties and regimes is that of the Lavas and their

successors. It is certainly not the Communist Party of the

Philippines, reestablished in 1968. But the imperialists, the

bourgeois mass media and certain other quarters wish to confuse

the situation and try to mock at and shame the Party for the

disintegration of the revisionist ruling parties and regimes.

They are barking at the wrong tree.

There are elements who have been hoodwinked by such catchphrases

of Gorbachovite propaganda as "socialist renewal", "perestroika",

"glasnost" and "new thinking" and who have refused to recognize

the facts and the truth about the Gorbachovite swindle even after

1989, the year when modern revisionism started to give way to the

open and blatant restoration of capitalism and bourgeois

dictatorship. There are a handful of elements within the Party

who continue to follow the already proven anticommunist,

antisocialist and pseudodemocratic example of Gorbachov and who

question and attack the vanguard role of the working class

through the Party, democratic centralism, the essentials of the

revolutionary movement, and the socialist future of the

Philippine revolutionary movement. Their line is aimed at nothing

less than the negation of the basic principles of the Party and

therefore the liquidation of the Party.

I. The Party's Marxist-Leninist Stand Against Modern

Revisionism

The proletarian revolutionary cadres of the Party who have

continuously adhered to the Marxist-Leninist stand against modern

revisionism and have closely followed the developments in the

Soviet Union and Eastern Europe since the early 1960s are not

surprised by the flagrant antisocialist and antidemocratic

outcome of modern revisionism. The Party should never forget that

its founding proletarian revolutionary cadres had been able to

work with the remnants of the old merger Party of the Communist

and Socialist parties since early 1963 only for so long as there

was common agreement that the resumption of the anti-imperialist

and antifeudal mass struggle meant the resumption of the

new-democratic revolution through revolutionary armed struggle

and that the old merger party would adhere to the revolutionary

essence of Marxism-Leninism and reject the Khrushchovite

revisionist line of bourgeois populism and pacifism and the

subsequent Khrushchovism without Khrushchov of the Brezhnev

regime.

So, in April 1967 when the Lava revisionist renegades violated

the common agreement and ignored the Executive Committee that had

been formed in 1963, it became necessary to lay the ground for

the reestablishment of the Party as a proletarian revolutionary

party. Everyone can refer to the diametrically opposed

proclamations of the proletarian revolutionaries and the Lava

revisionist renegades which were disseminated in the Philippines

and published respectively in Peking (Beijing) Review and the

Prague Information Bulletin within the first week of May 1967.

The reestablishment of the Party on the theoretical foundation of

Marxism-Leninism on December 26, 1968 necessarily meant the

criticism and repudiation of all the subjectivist and opportunist

errors of the Lava revisionist group and the modern revisionism

practised and propagated by this group domestically and by one

Soviet ruling clique after another internationally.

The criticism and repudiation of modern revisionism are a

fundamental component of the reestablishment and rebuilding of

the Party and are inscribed in the basic document of

rectification, "Rectify Errors and Rebuild the Party" and the

Program and Constitution of the Party. These documents have

remained valid and effective. No leading organ of the CPP has

ever had the power and the reason to reverse or reject the

criticism and repudiation of modern revisionism by the Congress

of Reestablishment in 1968.

In the late 1970s, the Party decided to expand the international

relations of the revolutionary movement in addition to the

Party's relations with Marxist-Leninist parties and organizations

abroad. The international representative of the National

Democratic Front began to explore possibilities for the NDF to

act like the Palestinian Liberation Organization, African

National Congress and other national liberation movements in

expanding friendly and diplomatic relations with all forces

abroad that are willing to extend moral and material support to

the Philippine revolutionary struggle on any major issue and to

whatever extent. This line in external relations was in

consonance with the Marxist-Leninist stand of the Party and the

international united front against imperialism.

In 1983, a definite proposal to the Central Committee came up

that the NDF or any of its member organizations vigorously seek

friendly relations with the ruling parties in the Soviet Union

and Eastern Europe as well as with parties and movements closely

associated with the CPSU. However, this proposal was laid aside

in favor of the counterproposal made by the international liaison

department (ILD) of the Party Central Committee that the Party

rather than the NDF explore and seek "fraternal" relations with

the ruling parties of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe and

other related parties.

Veering Away from the Antirevisionist Line

This counterproposal disregarded the fact that the Lava

revisionist group had already preempted our Party from the

possibility of "fraternal" relations with the revisionist ruling

parties. More significantly, the counterproposal did not take

into serious consideration the Marxist-Leninist stand of the

Party against modern revisionism.

Notwithstanding the ill-informed and unprincipled basis for

seeking "fraternal" relations with the revisionist ruling parties

and the absence of any congress withdrawing the correct

antirevisionist line, the staff organ in charge of international

relations proceeded in 1984 to draft and circulate a policy

paper, "The Present World Situation and the CPP's General

International Line and Policies" describing the CPSU as a

Marxist-Leninist party, the Soviet Union as the most developed

socialist country and as proletarian internationalist rather than

social-imperialist, as having supported third world liberation

movements and as having attained military parity with the United

States. This policy paper was presented to the 1985 Central

Committee Plenum and the latter decided to conduct further

studies on it.

In 1986, the Executive Committee of the Central Committee

commissioned a study of the Soviet Union and East European

countries. The study was superficial. It was done to support the

predetermined conclusion that these countries were socialist

because their economies were still dominated by state-owned

enterprises and these enterprises were still growing and because

the state still provided social guarantees to the people. The

study overlooked the fact that the ruling party in command of the

economy was no longer genuinely proletarian and that state-owned

enterprises since the time of Khrushchov had already become

milking cows of corrupt bureaucrats and private entrepreneurs who

colluded under various pretexts to redirect the products to the

"free" (private) market.

By this time, the attempt to deviate from the antirevisionist

line of the Party was clearly linked to the erroneous idea that

total victory in the Philippine revolution could be hastened by

"regularizing" the few thousands of NPA fighters with

importations of heavy weapons and other logistical requisites

from abroad, by skipping stages in the development of people's

war and in building the people's army and by arousing the forces

for armed urban insurrection in anticipation of some sudden "turn

in the situation" to mount a general uprising.

There was the notion that the further development of the people's

army and the people's war depended on the importation of heavy

weapons and getting logistical support from abroad and that the

failure to import these would mean the stagnation or

retrogression of the revolutionary forces because there is no

other way by which the NPA could overcome the enemy's

"blockhouse" warfare and control of the highways except through

the use of sophisticated heavy weapons (antitank and laser-guided

missiles) which necessarily have to be imported from abroad.

In the second half of 1986, with the approval of the Party's

central leadership, a drive was started to seek the establishment

of "fraternal" relations with the CPSU and other revisionist

ruling parties as well as nonruling ones close to the CPSU. A

considerable amount of resources was allotted to and expended on

the project.

In late 1986, some Brezhnevites within the CPSU and some other

quarters made the suggestion that the Communist Party of the

Philippines merge with the Lava revisionist group in order to

gain "fraternal" relations with the CPSU. But such a suggestion

was tactfully rejected with the countersuggestion that the CPSU

and other revisionist ruling parties could keep their fraternal

relations with the Lava group while the CPP could have friendly

relations with them. We stood pat on the Leninist line of

proletarian party-building.

Up to 1987 the failure to establish relations with the

revisionist ruling parties was interpreted by some elements as

the result of the refusal on the part of our Party to repudiate

its antirevisionist line. These elements had to be reminded in

easily understood practical terms that if the antirevisionist

line of the Party had been withdrawn and the revisionist ruling

parties would continue to rebuff our offer of "fraternal" or

friendly relations with them, then the proposed opportunism would

be utterly damaging to the Party.

By 1987, the Party became aware that the Gorbachov regime was

already laying the ground for the emasculation of the revisionist

ruling parties in favor of an openly bourgeois state machinery in

the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe by allowing his advisors,

officials of the Academy of Social Sciences and the official as

well as independent Soviet mass media to promote pro-imperialist,

anticommunist and antisocialist ideas under the guise of social

democracy and "liberal" communism. On the occasion of the 70th

anniversary of the October Revolution, Gorbachov himself

delivered a speech abandoning the anti-imperialist struggle and

describing imperialism as having shed off its violent character

in an integral world in which the Soviet Union and the United

States and other countries can cooperate in the common interest

of humanity's survival.

In 1987, the chairman of the Party's Central Committee made an

extensive interview on the question of establishing relations

with the ruling parties of the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and

elsewhere. This was made in response to the demand from some

quarters within the Party that the Party repudiate its line

against revisionism and apologize to the CPSU for having

criticized the Soviet Union on the question of Cambodia and

Afghanistan. The interview clarified that the Party can establish

friendly relations with the ruling parties even while the latter

maintained their "fraternal" relations with the Lava group.

Failed Efforts at Establishing Relations

In June 1988, the "World Situation and Our Line" was issued to

replace "The Present World Situation and the CPP's General

International Line and Policies". The correct and positive side

of the new document reiterated the principles of national

integrity, independence, equality noninterference and mutual

support and mutual benefit to guide the Party's international

relations; and upheld the basic principles of socialism,

anti-imperialism and proletarian internationalism and peaceful

coexistence as a diplomatic policy. Furthermore, it noted and

warned against the unhealthy trends of cynicism, anticommunism,

nationalism, consumerism, superstition, criminality and the like

already running rampant in the countries ruled by the revisionist

parties.

The negative side included accepting at face value and endorsing

the catchphrases of Gorbachov; describing the revisionist regimes

as socialist under a "lowered" definition; and diplomatic

avoidance of the antirevisionist terms of the Party.

In the course of trying to establish friendly relations with the

revisionist ruling parties in 1987 and onward, Party

representatives were able to discern that Gorbachov and his

revisionist followers were reorganizing these parties towards

their eventual weakening and dissolution. Despite Gorbachov's

avowed line of allowing the other East European ruling parties to

decide matters for themselves, Soviet agents pushed these parties

to reorganize themselves by replacing Brezhnevite holdovers at

various levels with Gorbachovites and subsequently paralyzed the

Party organizations. However, it would be in 1989 that it became

clear without any doubt that all the revisionist ruling parties

and regimes were on the path of self-disintegration, blatant

restoration of capitalism and bourgeois dictatorship under the

slogans of "multiparty democracy" and "economic reforms".

It is correct for the Party to seek friendly relations with any

foreign party or movement on the basis of anti-imperialism. But

it is wrong to go into any "fraternal" relations involving the

repudiation of the Party's Marxist-Leninist stand against modern

revisionism.

In this regard, we must be self-critical for wavering or

temporarily veering away from the Party's antirevisionist line

and engaging in a futile expedition. The motivation was to seek

greater material and moral support for the Filipino people's

revolutionary struggle. Although such motivation is good, it can

only mitigate but cannot completely excuse the departure from the

correct line. The error is a major one but it can be rectified

through education far more easily than other errors unless

ideological confusion over the developments in the Soviet Union

and Eastern Europe is allowed to continue. Most comrades assigned

to do international work were merely following the wrong line

from above.

The worst damage caused by the unconsummated and belated

flirtation with the revisionist ruling parties in the Soviet

Union and Eastern Europe is not so much the waste of effort and

resources but in the circulation of incorrect ideas, such as that

these parties were still socialist and that the availability or

nonavailability of material assistance from them, especially

heavy weapons, would spell the advance or stagnation and

retrogression of the Philippine revolutionary movement. It should

be pointed out that the Lava group had the best of relations with

these parties since the sixties but this domestic revisionist

group never amounted to anything more than being an

inconsequential toady of Soviet foreign policy and the Marcos

regime.

At this point, the central leadership and entirety of the Party

must renew their resolve to adhere to Marxism-Leninism and to the

antirevisionist line. We are in a period which requires profound

and farsighted conviction in the new democratic revolution as

well as the socialist revolution. This is a period comparable to

that when the classical revisionist parties disintegrated and it

seemed as if socialism had become a futile dream and the world

seemed to be merely a helpless object of imperialist oppression

and exploitation. But that period was exactly the eve of

socialist revolution.

II. The Legacy of Lenin and Stalin

The red flag of the Soviet Union has been brought down. The

czarist flag of Russia now flies over the Kremlin. It may only be

a matter of time that the body of the great Lenin is removed from

its mausoleum in the Red Square, unless Russia's new bourgeoisie

continue to regard it as a lucrative tourist attraction for

visitors with hard foreign currency.

The Soviet modern revisionists, from Khrushchov to Gorbachov, had

invoked the name of Lenin to attack Stalin. But in fact, the

total negation of Stalin was but the spearhead of the total

negation of Lenin and Leninism, socialism, the Soviet Union and

the entire course of Bolshevik and Soviet history. The

bourgeoisie in the former Soviet Union was not satisfied with

anything less than the open restoration of capitalism and the

imposition of the class dictatorship of the bourgeoisie.

It is necessary to refresh ourselves on the legacy of Lenin and

Stalin in the face of concerted attempts by the imperialists, the

modern revisionists, the barefaced restorationists of capitalism

and the anticommunist bourgeois intelligentsia to slander and

discredit it. The greatness of Lenin lies in having further

developed the three components of the theory of Marxism:

philosophy, political economy and scientific socialism. Lenin is

the great master of Marxism in the era of modern imperialism and

proletarian revolution.

He delved further into dialectical materialism, pointed to the

unity of opposites as the most fundamental law of material

reality and transformation and contended most extensively and

profoundly with the so-called "third force" subjectivist

philosophy (empirio-criticism). He analyzed modern imperialism

and put forward the theory of uneven development, which

elucidated the possibility of socialist revolution at the weakest

point of the world capitalist system. He elaborated on the

Marxist theory of state and revolution. He stood firmly for

proletarian class struggle and proletarian dictatorship against

the classical revisionists and actually led the first successful

socialist revolution.

The ideas of Lenin were tested in debates within the Second

International and within the Russian Social-Democratic Labor

Party (RSDLP). The proletarian revolutionary line that he and his

Bolshevik comrades espoused proved to be correct and victorious

in contention with various bourgeois ideas and formations that

competed for hegemony in the struggle against czarist autocracy.

We speak of the socialist revolution as beginning on November 7,

1917 because it was on that day that the people under the

leadership of the proletariat through the Bolshevik party seized

political power from the bourgeoisie. It was at that point that

the proletarian dictatorship was established. For this, Lenin is

considered the great founder of Soviet socialism. Proletarian

dictatorship is the first requisite for building socialism.

Without this power, socialist revolution cannot be undertaken. By

this power, Lenin was able to decree the nationalization of the

land and capital assets of the exploiting classes and take over

the commanding heights of the economy.

Proletarian class dictatorship is but another expression for the

state power necessary for smashing and replacing the state power

or class dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, for carrying out the

all-rounded socialist revolution and for preventing the

counterrevolutionaries from regaining control over society.

Proletarian dictatorship is at the same time proletarian

democracy and democracy for the entire people, especially the

toiling masses of workers and peasants. Without the exercise of

proletarian dictatorship against their class enemies, the

proletariat and the people cannot enjoy democracy among

themselves. Proletarian dictatorship is the fruit of the highest

form of democratic action-the revolutionary process that topples

the bourgeois dictatorship. It is the guarantor of democracy

among the people against domestic and external class enemies, the

local exploiting classes and the imperialists.

The Bolsheviks were victorious because they resolutely

established and defended the proletarian class dictatorship. They

had learned their lessons well from the failure of the Paris

Commune of 1871 and from the reformism and treason of the social

democratic parties in the Second International.

Wielding proletarian dictatorship, the Bolsheviks disbanded in

January 1918 the Constituent Assembly that had been elected after

the October Revolution but was dominated by the Socialist

Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks, because that assembly refused

to ratify the Declaration of the Rights of the Toiling and

Exploited People. The Bolsheviks subsequently banned the

bourgeois parties because these parties engaged in

counterrevolutionary violence and civil war against the

proletariat and collaborated with the foreign interventionists.

In his lifetime, Lenin led the Soviet proletariat and people and

the soviets of workers, peasants and soldiers to victory in the

civil war and the war against the interventionist powers from

1918 to 1921. He consolidated the Soviet Union as a federal union

of socialist republics and built the congresses of soviets and

the nationalities. As a proletarian internationalist, he

established the Third International and set forth the

anti-imperialist line for the world proletariat and all oppressed

nations and peoples.

In 1922 he proclaimed the New Economic Policy as a transitory

measure for reviving the economy from the devastation of war in

the quickest possible way and remedying the problem of "war

communism" which had involved requisitioning and rationing under

conditions of war, devastation and scarcity. Under the new

policy, the small entrepreneurs and rich peasants were allowed to

engage freely in private production and to market their products.

The Record of Stalin

Lenin died in 1924. He did not live long enough to see the start

of fullscale socialist economic construction. This was undertaken

by his successor and faithful follower Stalin. He carried it out

in accordance with the teachings of Marx, Engels and Lenin:

proletarian dictatorship and mass mobilization, public ownership

of the means of production, economic planning, industrialization,

collectivization and mechanization of agriculture, full

employment and social guarantees, free education at all levels,

expanding social services and the rising standard of living.

But before the socialist economic construction could be started

in 1929 with the first five-year economic plan, Stalin continued

Lenin's New Economic Policy and had to contend with and defeat

the Left Opposition headed by Trotsky who espoused the wrong line

that socialism in one country was impossible and that the workers

in Western Europe (especially in Germany) had to succeed first in

armed uprisings and that rapid industrialization had to be

undertaken immediately at the expense of the peasantry.

Stalin won out with his line of socialism in one country and in

defending the worker-peasant alliance. If Trotsky had his way, he

would have destroyed the chances for Soviet socialism by

provoking the capitalist powers, by breaking up the

worker-peasant alliance and by spreading pessimism in the absence

of any victorious armed uprisings in Western Europe.

When it was time to put socialist economic construction in full

swing, the Right opposition headed by Bukharin emerged to argue

for the continuation of the New Economic Policy and oppose Soviet

industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture. If

Bukharin had had his way, the Soviet Union would not have been

able to build a socialist society with a comprehensive industrial

base and a mechanized and collectivized agriculture and provide

its people with a higher standard of living; and would have

enlarged the bourgeoisie and the bourgeois nationalists in the

various republics and become an easier prey to Nazi Germany whose

leader Hitler made no secret of his plans against the Soviet

Union.

The first five-year economic plan was indeed characterized by

severe difficulties due to the following: the limited industrial

base to start with in a sea of agrarian conditions, the

continuing effects of the war, the economic and political

sanctions of the capitalist powers, the constant threat of

foreign military intervention, the burdensome role of the pioneer

and the violent reaction of the rich peasants who refused to put

their farms, tools and work animals under collectivization,

slaughtered their work animals and organized resistance. But

after the first five-year economic plan, there was popular

jubilation over the establishment of heavy and basic industries.

To the relief of the peasantry there was considerable

mechanization of agriculture, especially in the form of tractor

stations. There was marked improvement in the standard of living.

In 1936, a new constitution was promulgated. As a result of the

successes of the economic construction and in the face of the

actual confiscation of bourgeois and landlord property and the

seeming disappearance of exploiting classes by economic

definition, the constitution declared that there were no more

exploiting classes and no more class struggle except that between

the Soviet people and the external enemy. This declaration would

constitute the biggest error of Stalin. It propelled the

petty-bourgeois mode of thinking in the new intelligentsia and

bureaucracy even as the proletarian dictatorship was exceedingly

alert to the old forces and elements of counterrevolution.

The error had two ramifications.

One ramification abetted the failure to distinguish

contradictions among the people from those between the people and

the enemy and the propensity to apply administrative measures

against those loosely construed as enemies of the people. There

were indeed real British and German spies and bourgeois

nationalists engaged in counterrevolutionary violence. They had

to be ferreted out. But this was done by relying heavily on a

mass reporting system (based on patriotism) that fed information

to the security services. And the principle of due process was

not assiduously and scrupulously followed in order to narrow the

target in the campaign against counterrevolutionaries and punish

only the few who were criminally culpable on the basis of

incontrovertible evidence. Thus, in the 1936-38 period,

arbitrariness victimized a great number of people. Revolutionary

class education through mass movement under Party leadership was

not adequately undertaken for the purpose of ensuring the high

political consciousness and vigilance of the people.

The other ramification was the promotion of the idea that

building socialism was a matter of increasing production,

improving administration and technique, letting the cadres decide

everything (although Stalin never ceased to speak against

bureaucratism) and providing the cadres and experts and the

toiling masses with ever increasing material benefits. The new

intelligentsia produced by the rapidly expanding Soviet

educational system had a decreasing sense of the proletarian

class stand and an increasing sense that it was sufficient to

have the expertise and to become bureaucrats and technocrats in

order to build socialism. The old and the new intelligentsia were

presumed to be proletarian so long as they rendered bureaucratic

and professional service. There was no recognition of the fact

that bourgeois and other antiproletarian ideas can persist and

grow even after the confiscation of bourgeois and landlord

property.

To undertake socialist revolution and construction in a country

with a large population of more than 100 nationalities and a huge

land mass, with a low economic and technological level as a

starting point, ravaged by civil war and ever threatened by local

counterrevolutionary forces and foreign capitalist powers, it was

necessary to have the centralization of political will as well as

centralized planning in the use of limited resources. But such a

necessity can be overdone by a bourgeoisie that is reemergent

through the petty bourgeoisie and can become the basis of

bureaucratism, decreasing democracy in the process of

decision-making. The petty bourgeoisie promotes the bureaucratism

that gives rise to and solidifies the higher levels of the

bureaucrat bourgeoisie and that alienates the Party and the state

from the people. Democratic centralism can be made to degenerate

into bureaucratic centralism by the forces and elements that run

counter to the interests of the proletariat and all working

people.

In world affairs, Stalin encouraged and supported the communist

parties and anti-imperialist movements in capitalist countries

and the colonies and semicolonies through the Third

International. And from 1935 onward, he promoted internationally

the antifascist Popular Front policy. Only after Britain and

France spurned his offer of antifascist alliance and continued to

induce Germany to attack the Soviet Union did Stalin decide to

forge a nonaggression pact with Germany in 1939. This was a

diplomatic maneuver to forestall a probable earlier Nazi

aggression and gain time for the Soviet Union to prepare against

it.

Stalin made full use of the time before the German attack in 1941

to strengthen the Soviet Union economically and militarily as

well as politically through patriotic calls to the entire Soviet

people and through concessions to conservative institutions and

organizations. For instance, the Russian Orthodox Church was

given back its buildings and its privileges. There was marked

relaxation in favor of a broad antifascist popular front.

In the preparations against fascist invasion and in the course of

the Great Patriotic War of 1941-45, the line of Soviet patriotism

further subdued the line of class struggle among the old and new

intelligentsia and the entire people. The Soviet people united.

Even as they suffered a tremendous death casualty of 20 million

and devastation of their country, including the destruction of 85

percent of industrial capacity, they played the pivotal role in

defeating Nazi Germany and world fascism and paved the way for

the rise of several socialist countries in Eastern Europe and

Asia and the national liberation movements on an unprecedented

scale. In the aftermath of World War II, Stalin led the economic

reconstruction of the Soviet Union. Just as he succeeded in

massive industrialization from 1929 to 1941 (only 12 years)

before the war, so he did again from 1945 to 1953 (only eight

years) but this time with apparently no significant resistance

from counterrevolutionaries. In all these years of socialist

construction, socialism proved superior to capitalism in all

respects.

In 1952, Stalin realized that he had made a mistake in

prematurely declaring that there were no more exploiting classes

and no more class struggle in the Soviet Union, except the

struggle between the people and the enemy. But it was too late,

the Soviet party and state were already swamped by a large number

of bureaucrats with waning proletarian revolutionary

consciousness. These bureaucrats and their bureaucratism would

become the base of modern revisionism.

When Stalin died in 1953, he left a Soviet Union that was a

politically, economically, militarily and culturally powerful

socialist country. He had successfully united the Soviet people

of the various republics and nationalities and had defended the

Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. He had rebuilt an industrial

economy, with high annual growth rates, with enough homegrown

food for the people and the world's largest production of oil,

coal, steel, gold, grain, cotton and so on.

Under his leadership, the Soviet Union had created the biggest

number of research scientists, engineers, doctors, artists,

writers and so on. In the literary and artistic field, social

realism flourished while at the same time the entire cultural

heritage of the Soviet Union was cherished.

In foreign policy, Stalin held the U.S. forces of aggression at

bay in Europe and Asia, supported the peoples fighting for

national liberation and socialism, neutralized what was otherwise

the nuclear monopoly of the United States and ceaselessly called

for world peace even as the U.S.-led Western alliance waged the

Cold War and engaged in provocations. It is absolutely necessary

to correctly evaluate Stalin as a leader in order to avoid the

pitfall of modern revisionism and to counter the most strident

anticommunists who attack Marxism-Leninism under the guise of

anti-Stalinism. We must know what are his merits and demerits. We

must respect the historical facts and judge his leadership within

its own time, 1924 to 1953.

It is unscientific to make a complete negation of Stalin as a

leader in his own time and to heap the blame on him even for the

modern revisionist line, policies and actions which have been

adopted and undertaken explicitly against the name of Stalin and

have - at first gradually and then rapidly - brought about the

collapse of the Soviet Union and the restoration of capitalism.

Leaders must be judged mainly for the period of their

responsibility even as we seek to trace the continuities and

discontinuities from one period to another.

Stalin's merits within his own period of leadership are principal

and his demerits are secondary. He stood on the correct side and

won all the great struggles to defend socialism such as those

against the Left opposition headed by Trotsky; the Right

opposition headed by Bukharin, the rebellious rich peasants, the

bourgeois nationalists, and the forces of fascism headed by

Hitler. He was able to unite, consolidate and develop the Soviet

state. After World War II, Soviet power was next only to the

United States. Stalin was able to hold his ground against the

threats of U.S. imperialism. As a leader, he represented and

guided the Soviet proletariat and people from one great victory

to another.

III. The Process of Capitalist Restoration

The regimes of Khrushchov, Brezhnev and Gorbachov mark the three

stages in the process of capitalist restoration in the Soviet

Union, a process of undermining and destroying the great

accomplishments of the Soviet proletariat and people under the

leadership of Lenin and Stalin. This process has also encompassed

Eastern Europe.

The Khrushchov regime laid the foundation of Soviet modern

revisionism and overthrew the proletarian dictatorship. The

Brezhnev regime fully developed modern revisionism for a far

longer period of time and completely converted socialism into

monopoly bureaucrat capitalism. And the Gorbachov regime brought

the work of modern revisionism to the final goal of wiping out

the vestiges of socialism and entirely dismantling the socialist

facade of the revisionist regimes in Eastern Europe and the

Soviet Union. He destroyed the Soviet Union that Lenin and Stalin

had built and defended.

To restore capitalism, the Soviet revisionist regimes had to

revise the basic principles of socialist revolution and

construction and to go through stages of camouflaged

counterrevolution in a period of 38 years, 1953 to 1991. It is a

measure of the greatness of Lenin and Stalin that their

accomplishments in 36 years of socialist revolution and

construction took another long period of close to four decades to

dismantle. Stalin spent a total of 20 years in socialist

construction. The revisionist renegades took a much longer period

of time to restore capitalism in the Soviet Union.

In the same period of time, the revisionist regimes cleverly took

the pretext of attacking Stalin in order to attack the

foundations of Marxist-Leninist theory and practice and

eventually condemn Lenin himself and the entire course of Soviet

history and finally destroy the Soviet Union. The revisionist

renegades in their protracted "de-Stalinization" campaign blamed

Stalin beyond his lifetime for their own culpabilities and

failures. For instance, they aggravated bureaucratism in the

service of capitalist restoration but they still blamed the

long-dead Stalin for it.

Tito of Yugoslavia had the unique distinction of being the

pioneer in modern revisionism. In opposing Stalin, he deviated

from the basic principles of socialist revolution and

construction in 1947 and received political and material support

from the West. He refused to undertake land reform and

collectivization. He preserved and promoted the bourgeoisie

through the bureaucracy and private enterprise, especially in the

form of private cooperatives.

He considered as key to socialism not the public ownership of the

means of production, economic planning and further development of

the productive forces but the immediate decentralization of

enterprises; the so-called workers' self-management that actually

combined bureaucratism and anarchy of production; and the

operation of the free market (including the goods imported from

Western countries) upon the existent and stagnant level of

production. In misrepresenting Lenin's New Economic Policy as the

very model for socialist economic development, he was the first

chief of state to use the name of Lenin against both Lenin and

Stalin.

First Stage: The Khrushchov Regime, 1953-64

To Khrushchov belongs the distinction of being the pioneer in

modern revisionism in the Soviet Union, the first socialist

country in the history of mankind, and of being the most

influential in promoting modern revisionism on a world scale.

Khrushchov's career as a revisionist in power started in 1953. He

was a bureaucratic sycophant and an active player in repressive

actions during the time of Stalin. To become the first secretary

of the CPSU and accumulate power in his hands, he played off the

followers of Stalin against each other and succeeded in having

Beria executed after a summary trial. He depended on the new

bourgeoisie that had arisen from the bureaucracy and the new

intelligentsia.

In 1954, he had already reorganized the CPSU to serve his

ideological and political position. In 1955, he upheld Tito

against the memory of Stalin, especially on the issue of

revisionism. In 1956, he delivered before the 20th Party Congress

his "secret" speech against Stalin, completely negating him as no

better than a bloodthirsty monster and denouncing the

"personality cult". The congress marked the overthrow of the

proletarian dictatorship. In 1957, he used the armed forces to

defeat the vote for his ouster by the Politburo and thereby made

the coup to further consolidate his position.

In 1956, the anti-Stalin diatribe inspired the anticommunist

forces in Poland and Hungary to carry out uprisings. The

Hungarian uprising was stronger and more violent. Khrushchov

ordered the Soviet army to suppress it, chiefly because the

Hungarian party leadership sought to rescind its political and

military ties with the Soviet Union.

But subsequently, all throughout Eastern Europe under Soviet

influence, it became clear that it was alright to the Soviet

ruling clique for the satellite regimes to adopt

capitalist-oriented reforms (private enterprise in agriculture,

handicraft and services, dissolution of collective farms even

where land reform had been carried out on a narrow scale and, of

course, the free market) like Yugoslavia along an anti-Stalin

line. The revisionist regimes were, however, under strict orders

to remain within the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA)

and the Warsaw Pact.

The unremoulded social-democratic and petty-bourgeois sections of

the revisionist ruling parties in Eastern Europe started to kick

out genuine communists from positions of leadership in the state

and party under the direction of Khrushchov and under the

pressure of anticommunist forces in society. It must be recalled

that the so- called proletarian ruling parties were actually

mergers of communists and social-democrats put into power by the

Soviet Red Army. At the most, there were only a few years of

proletarian dictatorship and socialist economic construction

before Khrushchov started in 1956 to enforce his revisionist line

in the satellite parties and regimes.

The total negation of Stalin by Khrushchov was presented as a

rectification of the personality cult, bureaucratism and

terrorism; and as the prerequisite for the efflorescence of

democracy and civility, rapid economic progress that builds the

material and technological foundation of communism in twenty

years, the peaceful form of social revolution from an

exploitative system to a nonexploitative one, detente with the

United States, nuclear disarmament step by step and world peace,

a world without wars and arms.

Khrushchov paid lip service to proletarian dictatorship and the

basic principles of socialist revolution and construction but at

the same time introduced a set of ideas to undermine them. He

used bourgeois populism, declaring that the CPSU was a party of

the whole people and the Soviet state was a state of the whole

people on the anti-Marxist premise that the tasks of proletarian

dictatorship had been fulfilled. He used bourgeois pacifism,

declaring that it was possible and preferable for mankind to opt

for peaceful transition to socialism and peaceful economic

competition with the capitalist powers in order to avert the

nuclear annihilation of humanity; raising peaceful coexistence

from the level of diplomatic policy to that of the general line

governing all kinds of external relations of the Soviet Union and

the CPSU; and denying the violent nature of imperialism.

In the economic field, he used the name of Lenin against Lenin

and Stalin by misrepresenting Lenin's New Economic Policy as the

way to socialism rather than as a transitory measure towards

socialist construction. He carried out decentralization to some

degree, he autonomized state enterprises and promoted private

agriculture and the free market. The autonomized state

enterprises became responsible for their own cost and profit

accounting and for raising the wages and bonuses on the basis of

the profits of the individual enterprise. The private plots were

enlarged and large areas of land (ranging from 50 to 100

hectares) were leased to groups, usually households. Many tractor

stations for collective farms were dissolved and agricultural

machines were turned over to private entrepreneurs. The free

market in agricultural and industrial products and services was

promoted.

In the same way that the revisionist rhetoric of Khrushchov

overlapped with Marxist-Leninist terminology, socialism

overlapped with capitalist restoration. The socialist system of

production and distribution was still dominant for a while. Thus,

the Soviet economy under Khrushchov still registered high rates

of growth. But the regime took most pride in the higher rate of

growth in the private sector which benefited from cheap energy,

transport, tools and other supplies from the public sector and

which was credited with producing the goods stolen from the

public sector.

In the autonomization of state enterprises, managers acquired the

power to hire and fire workers, transact business within the

Soviet Union and abroad; increase their own salaries, bonuses and

other perks at the expense of the workers; lessen the funds

available for the development of other parts of the economy; and

engage in bureaucratic corruption in dealing with the free

market.

With regard to private agriculture, propaganda was loudest on the

claim that it was more productive than the state and collective

farms. The reemergent rich peasants were lauded. But in fact, the

corrupt bureaucrats and private farmers and merchants were

colluding in underpricing and stealing products (through

pilferage and wholesale misdeclaration of goods as defective)

from the collective and state farms in order to rechannel these

to the free market. In the end, the Soviet Union would suffer

sharp reductions in agricultural production and would be

importing huge amounts of grain.

The educational system continued to expand, reproducing in great

numbers the new intelligentsia now influenced by the ideas of

modern revisionism and looking to the West for models of

efficient management and for quality consumer goods. In the arts

and in literature, social realism was derided and universal

humanism, pacifism and mysticism came into fashion.

The Khrushchov regime drew prestige from the advances of Soviet

science and technology, from the achievements in space technology

and from the continuing economic construction. All of these were

not possible without the prior work and the accumulated social

capital under the leadership of Stalin. Khrushchov went into

rapid housing and office construction which pleased the

bureaucracy.

The CPSU and the Chinese Communist Party were the main

protagonists in the great ideological debate. Despite

Khrushchov's brief reconciliation with Tito, the Moscow

Declaration of 1957 and the Moscow Statement of 1960 maintained

that modern revisionism was the main danger to the international

communist movement as a result of the firm and vigorous stand of

the Chinese and other communist parties.

Khrushchov extended the ideological debate into a disruption of

state-to-state relations between the Soviet Union and China. In

the Cuban missile crisis, he had a high profile confrontation

with Kennedy. He first took an adventurist and then swung to a

capitulationist position. With regard to Vietnam, he was opposed

to the revolutionary armed struggle of the Vietnamese people and

grudgingly gave limited support to them.

The deterioration of Soviet industry and the breakdown of

agriculture and bungling in foreign relations led to the removal

of Khrushchov in a coup by the Brezhnev clique. Brezhnev became

the general secretary of the CPSU and Kosygin became the premier.

The former would eventually assume the position of president.

Second Stage: The Brezhnev Regime, 1964-82

While Khrushchov was stridently anti-Stalin, Brezhnev made a

limited and partial "rehabilitation" of Stalin. If we link this

to the recentralization of the bureaucracy and the state

enterprises previously decentralized and the repressive measures

taken against the pro-imperialist and anticommunist opposition

previously encouraged by Khrushchov, it would appear that

Brezhnev was reviving Stalin's policies.

In fact, the Brezhnev regime was on the whole anti-Stalin, with

respect to the continuing line of promoting the Khrushchovite

capitalist-oriented reforms in the economy and the line of

developing an offensive capability "to defend the Soviet Union

outside of its borders". It is therefore false to say that the

18-year Brezhnev regime was an interruption of the anti-Stalin

line started by Khrushchov.

There is, however, an ideological error that puts both Khrushchov

and Brezhnev on board with Stalin. This is the premature

declaration of the end of the exploiting classes and class

struggle, except that between the enemy and the people. This line

served to obfuscate and deny the existence of an already

considerable and growing bourgeoisie in Soviet society and to

justify repressive measures against those considered as enemy of

the Soviet people for being opposed to the ruling clique.

Under the Brezhnev leadership, the Khrushchovite

capitalist-oriented reforms were pushed hard by the

Brezhnev-Kosygin tandem. Socialism was converted fully into state

monopoly capitalism, with the prevalent corrupt bureaucrats not

only increasing their official incomes and perks but taking their

loot by colluding with private entrepreneurs and even criminal

syndicates in milking the state enterprises. On an ever widening

scale, tradeable goods produced by the state enterprises were

either underpriced, pilfered or declared defective only to be

channeled to the private entrepreneurs for the free market.

Sales and purchase contracts with capitalist firms abroad became

a big source of kickbacks for state officials who deposited these

in secret bank accounts abroad. There was also a thriving

blackmarket in foreign exchange and goods smuggled from the West

through Eastern Europe, the Baltic and southern republics.

The corruption of the bureaucrat and private capitalists

discredited the revisionist ruling party and regime at various

levels. At the end of the Brezhnev regime, there was already an

estimated 30 million people engaged in private enterprise. Among

them were members of the families of state and party officials.

Members of the Brezhnev family themselves were closely

collaborating with private firms and criminal syndicates in

scandalous shady deals.

The state enterprises necessary for assuring funds for the ever

expanding central Soviet bureaucracy and for the arms race were

recentralized. A military-industrial complex grew rapidly and ate

up yearly far more than the conservatively estimated 20 percent

of the Soviet budget. The Brezhnev regime was obsessed with

attaining military parity with its superpower rival, the United

States.

The huge Soviet state that could have generated the surplus

income for reinvestment in more efficient and expanded civil

production of basic and nonbasic consumer goods, wasted the funds

on the importation of the high grade consumer goods for the upper

five per cent of the population (the new bourgeoisie), on

increasing amounts of imported grain, on the military-industrial

complex and the arms race, on the maintenance and equipment of

half a million troops in Eastern Europe and on other foreign

commitments in the third world. Among the commitments that arose

due to superpower rivalry was the assistance to the Vietnamese

people in the Vietnam war, Cuba, Angola and Nicaragua. Among the

commitments that arose due to the sheer adventurism of Soviet

social-imperialism was the dispatch of a huge number of Soviet

troops and equipment to Afghanistan at the time that the Soviet

Union was already clearly in dire economic and financial straits.

The hard currency for the importation of grain and high-grade

consumer goods came from the sale of some 10 percent of Soviet

oil production to Western countries and the income from military

sales to the oil-producing countries in the Middle East.

The Brezhnev regime used "Marxist-Leninist" phrasemongering to

disguise and legitimize the growth of capitalism within the

Soviet Union. Repressive measures were used against opponents of

the regime, including the pretext of psychiatric confinement.

These measures served the growth of bureaucrat monopoly

capitalism and constituted social fascism. The Brezhnev regime

introduced to the world a perverse reinterpretation of

proletarian dictatorship and proletarian internationalism, with

the proclamation of the Brezhnev doctrine of "limited

sovereignty" and Soviet-centered "international proletarian

dictatorship" on the occasion of the Soviet invasion of

Czechoslovakia in 1968. It was also on this occasion that the

Soviet Union came to be called social-imperialist, socialism in

words and imperialism in deed. With the same arrogance, Brezhnev

deployed hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops along the

Sino-Soviet border.

The Soviet Union under Brezhnev tried to keep a tight rein on its

satellites in Eastern Europe within the Warsaw Pact. Thus, it had

to expend a lot of resources of its own and those of its

satellites in maintaining and equipping half a million Soviet

troops in Eastern Europe. Clearly, the revisionist ruling parties

and regimes were not developing the lively participation and

loyalty of the proletariat and people through socialist progress

but were keeping them in bondage through bureaucratic and

military means in the name of socialism.

The Soviet Union under Brezhnev promoted the principle of

"international division of labor" within the CMEA. This meant the

enforcement of neocolonial specialization in certain lines of

production by particular member-countries other than the Soviet

Union. The relationship between the Soviet Union and the other

CMEA member-countries was no different from that between

imperialism and the semicolonies. This stunted the comprehensive

development of national economies of most of the member countries

although some basic industries had been built and continued to be

built.

Eventually, the Soviet Union started to feel aggrieved that it

had to deliver oil at prices lower than those of the world market

and receive off-quality goods in exchange. So, it continuously

made upward adjustments on the price of oil supplies to the CMEA

client states. At the same time, among the East European

countries, there had been the long-running resentment over the

shoddy equipment and other goods that they were actually getting

from the Soviet Union at a real overprice.

Before the 1970s, the Soviet Union encouraged capitalist-oriented

reforms in its East European satellites but definitely

discouraged any attempt by these satellites to leave the Warsaw

Pact. In the early 1970s, the Soviet Union itself wanted to have

a detente with the United States, clinch the "most favored

nation" (MFN) treatment, gain access to new technology and

foreign loans from the United States and the other capitalist

countries. However, in 1972, the Brezhnev regime was rebuffed by

the Jackson-Vannik amendment, which withheld MFN status from the

Soviet Union for preventing Jewish emigration. The regime then

further encouraged its East European satellites to enter into

economic, financial and trade agreements with the capitalist

countries.

During most of the 1970s, these revisionist-ruled countries got

hooked to Western investments, loans and consumer goods. In the

early 1980s, most of them fell into serious economic troubles as

a result of the aggravation of domestic economic problems and the

difficulties in handling their debt burden, which per capita in

most cases was even worse than that of the Philippines. Being

responsible for the economic policies and for their bureaucratic

corruption, the revisionist ruling parties and regimes became

discredited in the eyes of the broad masses of the people and the

increasingly anti-Soviet and anticommunist intelligentsia. The

pro-Soviet ruling parties in Eastern Europe had always been

vulnerable to charges of political puppetry, especially from the

direction of the anticommunist advocates of nationalism and

religion. In the 1970s and 1980s these parties conspicuously

degenerated from the inside in an all-round way through

bourgeoisification and became increasingly the object of public

contempt.

The United States kept on dangling the prospect of MFN status and

other economic concessions to the Soviet Union. Each time the

United States did so, it was able to get something from the

Soviet Union, like its commitment to the Helsinki Accord

(intended to provide legal protection to dissenters in the Soviet

Union) and a draft strategic arms limitation treaty but it never

gave the concessions that the Soviet Union wanted. The United

States simply wanted the Cold War to go on in order to induce or

compel the Soviet Union to waste its resources on the arms race.

The only significant concession that the Soviet Union continued

to get was the purchase of grain and the commercial credit

related to it.

When the CPP leadership decided to explore and seek relations

with the Soviet and East European ruling parties in the middle of

the 1980s, there was the erroneous presumption that the

successors of Brezhnev would follow an anti-imperialist line in

the Cold War of the two superpowers. Thus, the policy paper on

the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe praised the Brezhnev line in

hyperbolic terms.

Although the Gorbachov regime would pursue worse revisionist

policies than those of its predecessor, it would become a good

source of information regarding the principal and essential

character of the Brezhnev regime on a comprehensive range of

issues. By using this information from a critical

Marxist-Leninist point of view, we can easily sum up the Brezhnev

regime and at the same time know the antisocialist and

anticommunist direction of the Gorbachov regime in 1985-88.

The Third and Final Stage: The Gorbachov Regime, 1985-91

The Gorbachov regime from 1985 to 1991 marked the third and final

stage in the anti-Marxist and antisocialist revisionist

counterrevolution to restore capitalism and bourgeois

dictatorship.

It involved the prior dissolution of the ruling revisionist

parties and regimes in Eastern Europe, the absorption of East

Germany by West Germany and finally the banning and dispossession

of the CPSU and the disintegration of the Soviet Union no less,

after a dubious coup attempt by Gorbachov's appointees in the

highest state and party positions next only to his.

The counterrevolution was carried out in a relatively peaceful

manner. After all, the degeneration from socialism to capitalism

proceeded for 38 years. Within the last six years, the corrupt

bureaucrats masquerading as communists were ready to peel off

their masks, declare themselves as excommunists and even

anticommunists overnight and cooperate with the longstanding

anticommunists among the intelligentsia and the aggrieved broad

masses of the people in setting up regimes that were openly

bourgeois and antisocialist.

Because they were manipulated and directed by the big bourgeoisie

and the anticommunist intelligentsia, the mass uprisings in

Eastern Europe in 1989 cannot be simply and totally described as

democratic although it is also undeniable that the broad masses

of the people, including the working class and the

intelligentsia, were truly aggrieved and did rise up. The far

bigger mass actions that put Mussolini and Hitler into power or

the lynch mobs unleashed by the Indonesian fascists to massacre

the communists in 1965 do not make a fascist movement democratic.

In determining the character of a mass movement, we take into

account not only the magnitude of mass participation but also the

kind of class leadership involved. Otherwise, the periodic

electoral rallies of the bourgeois reactionary parties which

exclude the workers and peasants from power or even the Edsa mass

uprising cum military mutiny in 1986 would be considered totally

democratic, without the necessary qualifications regarding the

class leadership involved.

It is possible for nonviolent mass uprisings to arise and succeed

when their objective is not to really effect a fundamental change

of the exploitative social system, when one set of bureaucrats is

simply replaced by another set and when the incumbent set of

bureaucrats does not mind the change of administration. It was

only in Romania where there was bloodshed because it was not

completely within the reorganizing that had been done by the

Gorbachovites in 1987 to 1989 in Eastern Europe. Ceaucescu

resisted change as did Honecker to a lesser extent. In the

dissolution of the CPSU and the Soviet Unio