18098.jpg, image/jpeg, 400x320

A newly released investigation into the deadly scourge of Beri-beri in Haiti's National Penitentiary uncovered evidence that the clash between the manufacturing process used in U.S. processed rice and the traditional Haitian rice cooking method has been killing poor young men behind bars and leaving others morbidly ill. by Jeb Sprague and Eunida Alexandra*

18098.jpg, image/jpeg, 400x320

By early 2006, firefights brought on by Haitian National Police and United Nations incursions into the capital's poorest neighborhoods had become commonplace. The raids, deemed "operations" by authorities, and reportedly designed to flush out criminal gangs, often resulted in high civilian causalities.

In a recent scientific study in the British medical journal The Lancet, done through random spatial sampling, it was estimated that 8,000 people were killed in the greater Port-au-Prince area from March 2004 through early 2006 after Haiti's elected government was ousted.

Already overcrowded and antiquated Haitian prisons quickly became packed with poor young men, drastically worsening the health conditions inside. The national penitentiary in Port-au-Prince built for a capacity of 800 today holds over 2,000 prisoners.

Last April, the Lamp for Haiti Foundation, a Philadelphia-based non-profit organisation created to address both the health care and the human rights needs of Haiti's poor, commissioned an investigation into the mysterious Beri-beri deaths of otherwise young, healthy prisoners in the Haitian National Penitentiary.

Staff attorney Thomas Griffin and staff physician James Morgan were given access by the national director of prisons, Wilkens Jean, to the sickest prisoners to search for clues to the source of the outbreak.

Griffin, a Philadelphia-based immigration lawyer and human rights investigator, had repeatedly visited the Haitian National Penitentiary since February 2002. In November of 2004, taking part in a Miami University human rights delegation, he found that poor supporters of the elected Aristide government had come under severe repression, showing up in "mass graves, cramped prisons, no-medicine hospitals, corpse-strewn streets and maggot-infested morgues".

In an October 2005 investigation, Griffin met with over 80 U.S. deportees. While conducting a follow-up investigation in March 2006, he found that a deportee from the United States he had met in October, Jackson Thermidor, had just died of congestive heart failure brought on by Beri-beri. Further, based upon reports from prison officials as well as prisoners, Beri-beri appeared to be devastating the overcrowded prison population.

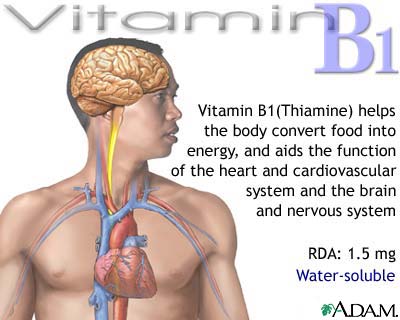

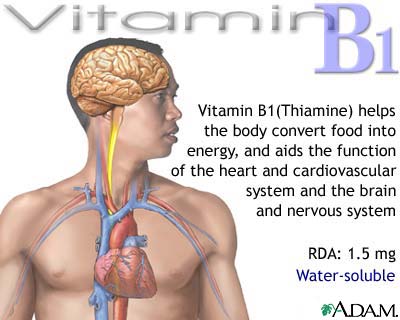

If left untreated, Beri-beri slowly attacks its victims' nervous systems, eventually causing congestive heart failure. Treatment, which is almost always successful, consists simply of the correct administration of a multivitamin supplement.

Morgan and Griffin observed that many of those arrested during the administration of the post-coup, foreign-appointed government started to suffer from weight loss, emotional disturbances, impaired sensory perception, weakness, pain in the limbs, and periods of rapid and irregular heartbeat -- all direct symptoms of Beri-beri.

Packed together in squalid conditions and provided meager, irregular meals, Haitian prisoners were fed a diet of rice that Griffin and Morgan discovered had lost its natural B1 vitamin/thiamin content, leading to the ultimately harmful effects. Griffin explained, "We found out that the little food they do give to prisoners is U.S.-processed rice."

All the Haitian rice production, which Haitians traditionally grew and consumed as a staple, was a healthy, whole-grain, vitamin B-packed, and native crop. But, due to U.S. policies since the early 1980's preferring U.S. rice producers over Haitians' own sustainable agriculture, tariffs were forced to drop, and U.S. rice flooded the Haitian market.

It not only destroyed much of traditional Haitian farm life that was the soul and lifeblood of the nation, but it pushed farmers off their land and into the city slums in Port-au-Prince. The prisoners, Griffin observed, who must eat the U.S. rice come from those slums, and are now dying of Beri-beri.

READ THE ENTIRE STORY