On October 27, 2005, a local Post Carbon meet up took place at Coco's restaurant on North Lake Avenue in Pasadena. A major part of the organization's mission is to find ways of surviving oil depletion and other crises (more information is at:

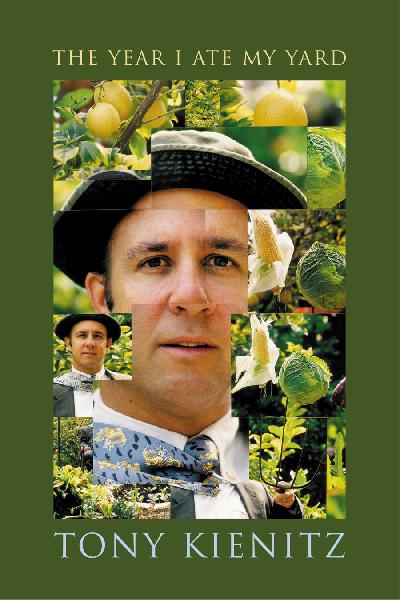

http://www.lapostcarbon.org/ and: www.postcarbon.org). Among the attendees was Tony Kienitz, author of the book The Year I Ate My Yard.

Unlike many of his public appearances, Kienitz this time delved into dark subjects such as global warming, oil depletion, and biotechnology. However, he also described positive actions people can take and offered a lot of advice about gardening and living harmoniously with nature.

TRANSCRIPT: TONY KIENITZ AT THE PASADENA POST CARBON MEETUP

Kienitz and five audience members, including the group organizer Eric Einem, are seated at a table in Coco's. The room is fairly quiet despite some dishes clattering and music playing over a speaker.

I ask Tony if he would mind me recording this event.

TONY KIENITZ: ...but you'll have the Supremes in the background, and any time you want to sing along...

ME: I'll include them in the transcript. I'm very thorough.

KIENITZ: Usually when I talk to groups I'm really upbeat and positive. I don't like to talk to larger groups of people and just be the big negative dude who steps in and tells them all the bad things that are going on in the world. Most people realize that Hell in a hand basket here we go.

ERIC EINEM: We know all about that.

KIENITZ: You do, I know. And you guys are kind of the kings of it because you know the worst.

OIL DEPLETION: "FROM MY POINT OF VIEW THAT'S NOT SUCH A BAD THING. . . "

But the last time I went to [a] permaculture meeting I was thinking about petroleum running out, that we're past the curve. From my point of view that's not such a bad thing, especially for agriculture. It's actually going to benefit our world of agriculture a lot because most of the pesticides are petroleum-based. [For] most of the industry that produces pesticides and fertilizers and fungicides and everything, the spine of their business is petroleum. They're going to have to change. So that's the good news about petroleum running out.

KIENITZ ON GLOBAL WARMING

Another thing that you're probably aware of [and for which] we've already passed the curve is global warming. We can't change it now. I have a really good friend at JPL [Jet Propulsion Laboratory] who's an arctic ice specialist. This summer's readings basically showed that the melting of the North Pole ice cap was significant enough that it won't be able to respond and freeze back enough. That's actually worse news than over-the-hill on petroleum because things are going to change rapidly in different parts of the world. Predicting what's going to change is going to be increasingly difficult.

It's not so much that the storms this year are that much of an anomaly, but the intensity and the number of storms world-wide has actually picked up, and the temperatures are really changing dramatically. So it's going to affect us here, it's going to affect us everywhere.

So that's how agriculture's going to change and how I do [my job].

". . . [A]S THE NEXT FEW YEARS GO BY, WE'RE ALL GOING TO BE MORE RESPONSIBLE FOR FEEDING OURSELVES. . . "

What I do is edible landscaping, primarily. I grow vegetable gardens, and orchards, and small vineyards for private homes and some public institutions as well. What I do becomes increasingly important, I believe, because as the next few years go by, we're all going to be more responsible for feeding ourselves for our own existence. What I do becomes increasingly important in the wealthier countries--like ours--to find a way to feed yourself. Some poor countries already know how to feed themselves a lot, but they don't [do it] because they rely on others

BIOTECHNOLOGY: ". . . [L]ACK OF DIVERSITY CREATES AN UNHEALTHY ENVIRONMENT."

The weirdest thing that's affecting us all right now, that not many people know about is biotechnology and bioengineering. [He points to the appetizer in the middle of the table.] These corn chips are bioengineered. We're eating bioengineered food every day, almost everybody is. I'm not suggesting that it's totally wrong. But what is occurring is a race between all of the major bioengineering companies around the world to develop and isolate a specific gene sequence in dandelions.

The dandelion is unique in the plant world because it hasn't changed at all in recorded history. It's very, very strange for a plant not to have offspring that are slightly different. There aren't any variegated... Do you know what variegated means? Variegated is a plant with white striping through it. It happens all the time in the plant world that a plant will grow green, green, green, and all of a sudden its leaves will have speckles of white. None of that happens in dandelions. The dandelions that Christ ate are the same as we're eating today.

What happens with a dandelion is it self-pollinates, just like tomatoes do. It provides its own fertilization, so it doesn't rely on its neighbors to reproduce itself. But what's really weird about the dandelion is it pollinates itself without pollen. Scientists still don't know how that's happening. They're able to isolate it over and over again so they can replicate it in certain ways, but then it falls apart in a different plant. So the gene sequence is what they're trying find [so] they can splice the genes that make the dandelion reproduce itself exactly without pollen.

[Then] they could splice that into broccoli. Now they don't need bees, now they don't need other insects, now they can spray certain insecticides that [affect] monarch butterflies.

Then they will create a type of broccoli, and that will be it. It will be the only broccoli because it will be commercially the strongest, most viable specimen available. And every single farmer will grow that same broccoli. It will be uniform from California straight around the world back to California.

It will take a few years, but the key is that the country that develops it first and that can put that gene into soy, and corn, and other staples first will dominate the world agricultural market. So if China does it first, China has no crop loss in the same significance that the U.S. does. It also has a uniform product that can be designed for packaging and designed for all this other stuff.

What I'm talking about is that rapidly--and we will see this within the next 10-15 years--somebody is going to hit the golden sequence, and there's going to be a mad rush to compete with that. And that country is going to take diversity right out of the picture. The problem with diversity going away, you can then have massive amounts of backlash: diseases can totally decimate a crop. Within a year you can have famines.

Also, lack of diversity creates an unhealthy

environment. Without diversity, the things that we

don't understand, because we're just at the beginning

of [understanding them], take over. So out of our lack of hubris we are creating these environments and scenarios that are going to be spooky.

I can foresee a time when the vast majority of people

are going to be at the whim of a seed company. They probably won't even know it. They'll still buy their chips. And there will be a few people in the world who still will be growing their own food or some of their own food. I think that's going to be incredibly important because pretty much all the seeds you and I can buy are owned by seed companies, except for just a few handfuls of specimens that are collected by individuals and saved by seed-saver groups. So that's what's in existence now. Once the genetics become involved, the amount of seeds that you or I or anybody will be able to buy will be reduced even further.

THE INCREASING IMPORTANCE OF BACKYARD HOBBYISTS

So starting to collect now [as a] backyard hobbyist is one of the things I'm going to start stressing to anybody who will listen. [Laughs.] It doesn't matter how much you grow. [Growing] one pot of a different heirloom lettuce right now is, I think, one of the few positive steps forward that you can do . . . . Just keep saving that, keep promoting that growth, and keep hoping that holds on.

. . . We can't really control the water quality; we can't really control the air quality; we can only be frustrated by the lack of insight in our commercial world; [and] we can't really, as individuals, control our politicians. But what we can still do is take our little space and do something positive, and growing something like that is [positive].

[He addresses the group.] Do you have a space of your own?

MALE: I have an apartment.

KIENITZ (to another audience member): Do you have a full garden?

MALE #2: I'm a renter, but I'm just planting stuff wherever I can.

KIENITZ (to another person): And do you have anything?

MALE #3: I'm also in an apartment, but it's cottage-style, so there's a little yard.

KIENITZ (to me): And do you have one?

ME: I have a small yard, and I rent also.

KIENITZ: I always tell renters to tell the landlord: "I'm improving your soil. It's just like painting: when I move out, I'll have to fix it up before I go."

Even if you live in an apartment on the second or third floor, there's usually a space there that you can adopt, and the landlord is almost always amenable to somebody trying something as long as you don't make it ratty and nasty.

FEMALE: I have the opposite problem, actually. I'm the landlord; I live on the property, and I rent half the property to somebody else. He wants to play baseball with a kid and wants a lawn.

KIENITZ: That's going to be a problem for everybody, too: space, especially for my kids. By the time they're in their twenties, they're going to be looking at much more density and water issues--definitely water issues.

WATER ISSUES IN THE FUTURE

That's another thing: going back to doom and gloom, paint me as an idiot, but I never put two and two together and realized that these giant diesel pumps [bring in our water]. Of course they do. I just never thought about it. When I realized that I had never even thought about it, then I realized how in the dark the vast majority of people must be.

[T]hen I asked a few people who didn't know either. Two people out of four or five said, "Well, it's just flowing downhill, and that's how it gets here." . . . That also, in their minds, accounted for water pressure, which I just thought was really fascinating. People just don't spend extraordinary time thinking about all these things.

THE FRAGILITY OF AMERICA'S AGRICULTURAL SYSTEM

But what people don't know about the food supply and water is that the American agricultural system is so tightly-fixed on a calendar that we only have about seven-to-nine days of leeway. So if we had three weeks of complete disaster--in California in particular because we produce the largest amount of fresh food for the country--our food system in the U.S. would completely disintegrate because it's all on such a tight schedule.

The beets come in, and everybody who's a producer of beets knows when [the] A-crop of beets comes in, B-crop, C-crop, D-crop. And it's all on a farm conveyor belt to processing plants, to shipping out to wherever.

If California is massively interrupted in that sequence, the rest of the country will quickly get blown out of the water.

QUESTION (ERIC EINEM): And what about grains?

KIENITZ: Grains? Well, you can stockpile grain. What we're told is we have lots of grain.

EINEM: How many weeks or months?

KIENITZ: Maybe years. That's why we can sell it to Russia and to...

EINEM: So we're not going to starve?

KIENITZ: No. It's not starving on grains, but it's starving on fresh greens: carrots and tomatoes and broccoli.

EINEM: You can go for a while without that, maybe not forever.

KIENITZ: Lots of people in this country go a long, long time without any of that. [Laughter.] Just drive through Texas. They wouldn't miss it at all.

But what will happen, though, is that, again, it's a matter of diversity. [He again gestures to the plate with chips and dip on it.] So this plate here, within a few weeks, would not be able to have salsa [he refers to one of the other dips] and within a few weeks would be able to have the cheese but would not be able to have the spinach [mixed in], because we would eat it up fast enough. There's millions of people eating the same exact foods. So then it would be chips and cheese. Then, eventually--and this would have to really go down the road--cheese would be so expensive that you wouldn't want to use it again. [If] you feed the grains to the cows, who gets the food?

SURVIVING A WATER CRISIS IN THE SOUTHWEST U.S.

But if the costs of pumping water into Southern California becomes higher than is affordable, then A) we're going to have to start collecting our own water in our backyards, which people will do with cisterns and stuff. And B) fresh food in the arid Southwest is going to be produced only by locals because shipping and bringing the water there is going to be really difficult. So people are going to start dry farming, people are going to collect their own water and grow in season. There's going to be a lot of change.

I think anybody who's progressively-minded should start thinking about how, just in the smallest little way they can, grow something in their space that they can eat, whether it's herbs or whatever, and go with it from there.

QUESTION: You mentioned dry farming. What is that?

KIENITZ: It's really hard, but the best tomatoes you will ever eat are dry-farmed. They pull in more mineral and they pull in more sugar somehow. The soil is massively worked. Permaculture would define it very well. Let's say you have a natural-occurring gully that will hold a farm which may be 15'wide by 150'long, is massively cropped right in this little area, and ambient water flows to it. [If there is no ambient water], what they sometimes do is carry buckets from a well to a plant that's absolutely emaciated from a lack of water.

Dry farming was a primary way of farming in Southern

California before the aqueducts. All the citrus can

grow that way. You just need to grow it in soils that

are more appropriate. Riverside had no water, and

that's were the citrus farms started. It had rocky,

rocky soil, that they busted all up, and it was

porous enough that the citrus could get going on it.

Once the orchards are established, then you do

orchard-growing. You grow intensively under the

drip lines of the trees: greens and things of that nature.

That's my spiel for the night.

DISCUSSION WITH GROUP

QUESTION: Did you get into this topic in the book that

you wrote?

KIENITZ: This topic about doomsday? No. Half

of the book was that, and then my mother-in-law made an editorial comment one night. She was saying: "You know, when I get to all the gloom-and-doom stuff, I just flip pages. I don't even read it." I realized that a good percentage of the people that were going to buy my book were going to be my mother-in-law.

I really, honestly believe that a lot of any movement

is based on how sexy or attractive you can make it to

people who are in that movement. Certainly there are

people who are strident in any movement or any kind of thinking that are going to carry the weight of the

real philosophy. But I thought it might be more

important to get people just willing to accept the

idea of eating organic food first and growing food.

These are two big leaps for most people anyway.

I think a lot of times people just end up preaching to

the choir. There's the book Believing Cassandra. Did you ever read that? Cassandra came along in the Greek tale and said, "The sky is falling, the sky is falling." Nobody wanted to believe her, and then they killed her after it came true.

GROUP MEMBER: She was cursed by the gods. They gave her the gift of prophecy, but the curse was nobody would ever believe her.

KIENITZ: Yeah, and then when it did come true, they killed her, right? So I don't want to be killed for telling these things [laughter].

But secondarily, what was great about that book was he [author Alan AtKisson]was writing about all the horrors of this world right now, the problems that are going on in third-world countries, [and] all the military things that are going on and always have. He spent only about 50 pages on that, and then he spent 300 or 200 on what to do about it, what to do with this information, how to change things. Over and over again he repeated the same idea, which I love, is "make the revolution attractive. And once it's attractive, then people will want to jump on." Most people don't want strain anything, or make any waves, or change in any way.

QUESTION: How much time would it take, though? Most people have to work nine to five or nine to six. When they get home, especially in winter, it's going to be dark.

KIENITZ: I agree. You do it simple, you recognize your constraints. I get home at the exact same time. I had a brutal day, I have actually had a brutal couple days. . . but I still ate a little bit from my garden tonight, and that's because it's at the back door in pots. So if I don't have a chance to go out and weed and do all the things every day, fine. I end up probably working an hour or two every Sunday and catch up a little bit.

My garden looks trashed almost all the time, unless somebody says, "Can we take photos of your yard for Such-and-Such magazine?" Then comes the wild rush to try and do something. Mulch! Mulch! Mulch! [Laughter.] But I'm just really forgiving of it.

The other thing, too, is that because I'm trying to grow something offbeat and rare, and things I've never grown before, it doesn't matter to me if the plant goes to seed and goes through it's whole lifespan... [A waiter apologetically interrupts to take people's orders.]

...A lot of people don't know that the arugula flowers are probably as good to eat or better than the arugula itself. The flowers really have a sweet flavor and are a delicacy that you just can't capture anywhere else. So why not?

People are really obsessed with being a farmer, and that's not what I'm talking about. I'm saying, grow a little bit for yourself so you understand it. That may help you to make sure you go to the farmer's market every Saturday and support a local grower and not just say, "Oh, I'm going to do that."

And it may make you be sure that you're going to ride your bike to the farmer's market on Saturday with sacks that you're going to drag home somehow. That's my goal, and I never make that goal. [Laughs.] I get to the farmer's market occasionally, but I don't get on the bike there often.

COMMENT: Speaking of livestock, did you know a lettuce plant is [inaudible] feet long?

KIENITZ: Every year I learn something, and now I'm experiencing this: the Romans never ate lettuce the way we eat lettuce. They waited for it to bolt. They wanted it bitter.

COMMENT: Bitter lettuce, it tastes fine.

KIENITZ: Yeah. Another thing, too: if you cook it, like you do any bitter green, it's fine.

So that's a funny thing. You would never be able to go to Ralphs and say: "Do you have any bolted lettuce? I've got this hankering for it." No way. You could do that at home, and you could decide you hate it, but at least you'd know. And the effort to fail with lettuce takes no effort at all [laughs]. Just sprinkle some water on it occasionally.

COMPOSTING: "THESE LITTLE STEPS THAT YOU CAN DO ARE JUST DRAMATIC."

Also, if you have a small garden space, even if it's in pots, you can compost it right there. You make a salad, and it's gone bad a little bit, you just put some water in there and put it in your blender, and you blend it up and pour it around the plants. What you're doing is recycling and not putting it into a landfill.

These little steps that you can do are just dramatic.

Also, you don't have to tell anybody you're doing it, that's the great thing. You don't have to go out and advertise and say: "Hey, look at me!" Because everybody catches on really fast.

VEGETARIANISM: "ONE OF THE BEST ARGUMENTS FOR VEGETARIANISM IS TO SAVE OIL."

[He turns to an audience member who has ordered a veggie burger.] Are you a vegetarian?

MALE: Not strictly.

KIENITZ: I've found that as soon as I stopped telling everybody I was a vegetarian, it was much better. People would just come out of the woodwork and go, "Oh wait, you're not eating meat?" I'd go "No," and I wouldn't talk about it. Then three minutes would go by, and they would go, "Well, why not?" "You don't want to know."

MALE: What if you're coming over for dinner? Do you tell them?

KIENITZ: Well, yeah. If you're coming over for dinner, you say: "Well, Tony's a vegetarian. You don't have to do anything special." And they totally freak out, [laughter] but that's okay.

MALE: They [think], "Okay, how do you make a vegetarian steak?"

KIENITZ: Exactly.

I don't know if you know [this], too, but one of the best arguments for vegetarianism is to save oil. The consumptive aspect of producing meat is obscene.

EINEM: Yes, for me, that's the easiest step I can take to reduce my ecological footprint. The biggest step would probably be to sell my car, but the easiest one is to not eat meat.

KIENITZ: Yes, and nobody has to know. It doesn't have to hurt anybody. Nobody really cares if you don't eat meat.

MALE: When I tell people at work that I'm almost a strict vegetarian (I still eat fish), they look at me like, "How can you do this?"

FEMALE: There are so many vegetarians, though. You wouldn't think they would be that surprised.

KIENITZ: It's still only one percent of the American population.

VARIOUS PEOPLE: Really?!

KIENITZ: And actually, there's probably two-to-three percent of the U.S. population that never eats anything but meat, that survives only on meat...

MALE: ...and a little bit of bread.

ME: Ten years ago, eating meat was kind of being glorified in those Carl's Jr. commercials. Remember the bumper stickers that said "Eat meat"?

KIENITZ: Oh yeah, and the Atkins' diet is coronary disease, so there you have it.

". . . AS SOON AS I STOPPED KILLING THINGS IN MY GARDEN--NO BUGS, NO SNAILS, NO SLUGS--THE GARDEN GOT A LOT HEALTHIER. . ."

The other thing about eating meat, and this goes further, as soon as I stopped killing things in my garden, really actively not killing things--no bugs no snails no slugs--the garden got a lot healthier because all of these creatures have natural predators, and I was screwing with the balance. I was providing all this lush food for the initial predators--the snails, the slugs--and before their natural predators come along, I'm pulling them out. I'm totally screwing up this environment, not giving it any time to actually find its own truth. As soon as I stopped killing anything, boom, the snails disappeared.

Now every once in a while, I'll go, "Oh, there's a snail," but I'm not worried about it. It's not out there just wiping me clean, which is really fascinating. I have snails and slugs in my garden, and I have 45 modest plants, and not one has been chewed on.

QUESTION: So what eats the snails?

KIENITZ: Lizards [and] disease in the compost.The compost has bacterium in it that [affects] snails. Because they are slimy, mucous-[covered?], they get diseases more rapidly than other creatures do. They also have a deficient immune system. You would think that they'd have evolved, but there's something about them that's not allowing them to do that.

So I recognized that all of a sudden I stopped killing

in my garden, and I thought about the bigger picture. I honestly think that we have things like Iraq happening because on some level we allow killing for no reason to occur in all of our lives. I go out and I smoosh snails. Well, how is that any different from dropping bombs on people that I'm never going to see? In a metaphorical way, it's kind of all the same. It's one life form, and I don't value that life form, and I'm not valuing that life form.

[Inaudible sentence.] I'm not building a marble house and walking around naked in an attempt not to kill a single thing, but I'm trying to actively avoid killing as much as I can.

KEEPING ANTS AWAY: "IT'S THE LITTLE THINGS THAT YOU DO OVER AND OVER AGAIN THAT ADD UP TO ONE BIGGER PICTURE."

ME: One issue I have is ants. I avoid killing them by moving anything that attracts them. Even if something doesn't need to be refrigerated, I'll put it in the refrigerator so the ants won't have anything to go after. Do you have any other ideas about keeping ants away?

KIENITZ: Yeah, Mule Team borax. You get it at a 99 Cents Store. If [ants] get any on them, a few of the first scouts are going to die from that, but it's a sure deterrent. It's a soap, but it's been mined forever, and I guess it's abundant. I've never heard of it being depleted or ruining ecosystems. You put it toward corners, especially at entrances, and you sweep it in. It doesn't take much at all, and it's a really strong deterrent.

And rosemary and other herbs, just crushed up and strewn for a day or two and brushed into the corners and then vacuumed up or brushed away, also help. It's about making them not want to come.

Your neighbor is going to have a huge influx of ants because of you, [laughs] and they may kill them all with spray. You don't know. But for a homeowner like myself or somebody who's in a single unit opposite of others, you can really make a difference.

ME: Well, I rent a single-unit house.

KIENITZ: Oh, well then you're good. You can just push them right outside.

EINEM: Also, I found that mud, wall putty, and whatever is very useful. I would just see where [the ants] were coming in, and I would go and cover it up.

KIENITZ: Yes, absolutely.

EINEM: That would keep them out for a couple months, and then they'd come in somewhere else, and I'd cover that up.

KIENITZ: Every once in a while I'll wake up late on a Sunday morning, I'll stumble into the kitchen for coffee, and there will be my wife killing ants. I just go: "OH! The carnage!" [Laughter.] What a way to wake up.

ME: One time a landlord was in my house, and there were all these ants on a wall, and she just wiped them out with a stroke of her arm. It reminded me of Godzilla because I was watching this from a low vantage point. [Laughter.]

KIENITZ: That's very funny. But anyway, it's something to think about, that your influence is greater than you think. It's the little things that you do over and over again that add up to one bigger picture. [Suggestions for deterring other pests can be found here:

http://www.organicformulations.com.au/repellent_recipes.asp ]

SEED SAVERS EXCHANGE: "YOU CAN FIND THE RAREST PLANT IN THE U.S. . . ."

[To group] Do you belong to the Seed Savers Exchange?

Another thing to look up on the internet just to know about, so you can recommend it to other people, is called Seed Savers Exchange (see:

http://www.seedsavers.org/ ). It's the largest seed-saving group in the United States. What's really great about it is you join for up for $25 or whatever, and then they send you the members catalog with people in Iowa; and people in Tallahassee, Florida; people in Maine, saying: "I have been growing chiogga beets. I'll sell you a packet for a dollar or the cost of postage or whatever." It's a telephone book thick of people who are doing this, and you can exchange.

What's really great is you can find the rarest plant in the U.S. like German cabbages that have been grown in that area since the Roman time and have been passed from family to family to family. They brought out all the Russian tomatoes. They were the ones who smuggled them in first in the '70s. It's really fun to look at.

And if you go to their website, then you get a feeling of what's going on. It just opens you up. I'm like a Trekkie, it's a whole new episode that you never knew about.

CORPORATE SEEDS

QUESTION: When a person goes to a garden center, like Armstrong, are those seeds Monsanto seeds? Are they big-business seeds, or would they come from small mom & pop [businesses]?

KIENITZ: All those [inaudible word] are corporate seeds, yes. Now Rene Shepherd is smaller, and she's California-based, but it's still corporate.

So based on the tier scenario of any corporate plan, those seeds that are offered are all being tested. And the number of seeds that are being bought are being charted and numbered. You may see a whirlwind of nasturtium this year, and that may be the last time it's ever offered because you're the only one who bought it. So unless you save those seeds yourself, they may go obsolete really quick. And that's what's happening with the seed companies in general.

QUESTION: These seed companies don't save them?

KIENITZ: They have a bank, but [the seeds] will just be sitting in the refrigerator vault forever. The[companies] may lose the strain themselves. They do plant out occasionally, just to keep the seeds viable, but they really use them based on economic vitality as well. So if there's a flower that hasn't sold ever or hasn't sold well for years and years and years, they'll let it go obsolete, they'll let it go extinct because it's not economically viable.

SAVING SEEDS: "AS SOON AS YOU GROW IT OUT, THAT SEED IS NOW AN INDIVIDUAL AGAIN. THAT'S WHAT COMPANIES AREN'T TELLING YOU."

QUESTION: Is there any merit in saving the seeds from those plants?

KIENITZ: Well, that's the interesting thing. The difference between a hybrid and an heirloom is an

heirloom is a seed that hasn't been crossed chemically by biotech scientists, a hybrid has. A hybrid has genetic qualities mixed from two different parents to create a different type of tomato. Hybrid tomatoes are most common in backyard gardens.

But if you take the seeds from a hybrid tomato, they always warn you that it won't grow true. That's not a problem at all, actually. Say you get a Lemon Boy. A Lemon Boy is mixed with a lemon tomato and a Better Boy tomato, so it has qualities of both. If you save the seeds from that, you don't know if it's going to be a red tomato, or a yellow tomato, or if it's going to be disease-resistant for [inaudible]. But what you are going to know is that it's going to be about the same size as [the parents]. And [if] you grow it out once, you can rename it the Dermott (sp?) because it's yours. As soon as you grow it out, that seed is now an individual again. That's what companies aren't telling you. What the companies are telling you is, "Don't grow it because it won't grow true." Well, you can grow these tomatoes over and over again.

The other difficulty, too, though is that in that same tomato they're also imprinting sterility. So a good 60-to-65% of the seeds in any plant that you grow out that's been a hybrid will be sterile. So you just have to be really patient. Throw a thousand seeds...

GROUP MEMBER: ...and you'll get 40%.

KIENITZ: Yeah.

QUESTION: Will the [offsprings] eventually become more fertile?

KIENITZ: Oh, absolutely. . . . And the amount of seeds in a single tomato number in the hundreds, so it doesn't take much time. Nature really produces much more than it needs to because it's hedging its bets as far as it can go.

EDIBLE WILD PLANTS: ". . . I HAVE THIS VISION OF PEOPLE LAYING DOWN HERE AND STARVING TO DEATH NEXT TO A DANDELION." -- POST CARBON ACTIVIST

[The subject segues to unproductive uses of land in our society.]

GROUP MEMBER: . . . People with these mansions at least have a quarter of an acre of land, but it's covered with grass, it's covered with a driveway for an SUV. And they will starve. They will actually lay on the ground and starve to death. (To Kienitz) I know you make salad from weeds, but I have this vision of people laying down here and starving to death next to a dandelion.

KIENITZ: Oh, yeah. I can't even watch that show Survivor because I'm like: "You idiot! You can eat that!"

QUESTION: Do you have weed salad recipes in your book?

KIENITZ: No, but I think Chris Nyerges in his book Extreme Simplicity has weed salad, and that book's at the Pasadena Library.

PLANNING FUTURE POST CARBON EVENTS: WORKSHOPS ON BEING SELF-SUFFICIENT

The formal discussion ends, and the conversation turns to future Post Carbon events. "There seems to be a fair amount of interest in doing a series of workshops [regarding] anything that would help us be more self-sufficient," Einem says. "Of course, a big part of that would be growing food. The idea is that this would make us more localized, which is one of the missions of our group. The thought I had was to make a series of workshops, where [we teach] whatever skills we have."

He lists what one member of Post Carbon can do: "gardening, acorn-preparation, canning, candle-making, wheel-thrown pottery and glaze-making, spinning [yarn?] crocheting,and sewing." Einem adds, "She's also interested in making a solar oven."

WHAT COULD PEOPLE CONTRIBUTE TO A LOCALIZED ECONOMY?

Various people describe what they could possibly contribute to the workshops. "I would be happy to share what little I know on the subject matter of gold," says a member, "if anyone is interested in having a financial buffer against currency meltdown, which I think is a valid fear. The more I read on From the Wilderness [

http://www.fromthewilderness.com/ ], I finally cracked. I was at work fidgeting like a crazy man because I was so scared. . . . Somebody asked Kenneth Deffeyes, who is one of the peak-oilers, what [they] should do about peak oil. His comment was 'Buy your gold in [inaudible]-ounce coins because it will be easier to make change.' Any of us that have any kind of liquid money should have 10% of our wealth in metals: gold, silver, platinum, palladium, whatever you can get your hands on. And then you can forget about it. Once I get it into my hands, which will be within the next few days, into a vault it goes, and then I forget about it. That's one thing I never have to worry about. That's my plane ticket home or whatever. That's the simplest thing any of us can do."

BUILD YOUR OWN SOLAR OVEN

Another subject discussed is building solar ovens. "I saw a great link [about] a solar oven you can make from a car windshield [shade cover]," says a member. "With Velcro tabs, you can take one of these windshield [shade covers] and loop it around into a dome shape, stick it on top of a plastic water bucket, and you can get it to 350 Fahrenheit, the same speed as a gas oven, basically.

"So many millions of people have them in this city. They'll probably be sitting around going, 'I can't cook my food,' and they have a solar oven sitting in their car. If you go to PathtoFreedom.com, they posted a link to that in their journal about five or six days ago. [Also, see:

http://unpluggedliving.com/windshield-shade-solar-oven/ ]. That's on my immediate to-do list." "We can do it at a workshop," says Einem.

"IF YOU HAVE GOOD COMPOST, THERE'S REALLY NOTHING ELSE YOU NEED." -- KIENITZ

A member expresses interest in learning about composting. "That's the magic trick," remarks Kienitz. "If you have good compost, there's really nothing else you need. The well-composted [gardens] are really active and really alive and jumping in there and kicking the soil around your plants into action. There's nothing you can buy, there's nothing you can do beyond that that isn't just miraculous. I've revived just the worst gardens with good compost--quickly."

Kienitz is asked how home-made compost compares with that which can be bought at stores. "It's much better," he replies. "For one, the plant sources [that the companies] are making it out of is mostly lumber-industry slough, and there'll be some cow manure, or horse manure, or landscape trimming, or street sweepings mixed in. But your's is going to have moldy blueberries that you didn't get to, a bell pepper that was bad, banana skins. It's going to have minerals and foods from all over, and then you're going to be able to find yarrow, or grow yarrow yourself, or buy even buy some dried yarrow, and put that in there. That's one of the magic ingredients in compost. Yarrow is a flower. It has an umbrellalike flower. That and stinging nettle. I like growing [stinging nettle], but you can buy it at Whole Foods. Seriously, just a handful of that in your compost... It's got compounds in it that make certain microorganisms in your compost healthier.

"You learn those little things: there's compost layer-layer-layer basics, and then you make sure you water it as often as you water your garden, and ka-boom! You're the genius gardener."

"WE COULD HAVE A LITTLE WORKSHOP ON MAINTAINING AND REPAIRING YOUR BIKE." -- EINEM

Other suggestions for workshops include medical uses for herbs. "Also, we have local bicyclists that know how to fix bikes," Einem says. "We could have a little workshop on maintaining and repairing your bike."

"I have never been on one of those fixed bikes . . . that new craze," says Kienitz. "I just want to try it." "The [name of a group, inaudible] were using one for milling grain," says a Post Carbon member, "and they want to pick up another one for generating power so that they can have a screening that's entirely powered by bicycle."

"With a lot of these [undertakings] I think there's a fear of starting a compost pile or even solar panels," remarks the same participant. "When you begin your first step towards doing something new or different in your life, you want somebody to tell you you: 'It's okay, it won't explode. Here's how I did it.' That gets people over that initial barrier of fear that they have to cross."

END

Tony Kienitz's website is at:

http://www.vegetare.com/ For more information about the local Post Carbon group, you can e-mail:

info@lapostcarbon.org.

-----

(1)Instead of eradicating bugs, snails, and slugs, "I would see them, and pick them up, and put them out of the garden, but I would not kill them," said Kienitz.